History of the dental chair

by Andrew I Spielman

How to cite this page: Spielman, AI. Place and means of practice. In: Illustrated Encyclopedia of the History of Dentistry. 2023. https://historyofdentistryandmedicine.com/

In the early era of dentistry, when tooth extraction prevailed as the primary treatment method, itinerant tooth drawers were common. Their tools were minimal, typically limited to forceps, and the procedure demanded little space or specialization. Ancient Romans practiced tooth extraction, though details about whether subjects sat on the floor or a chair are scarce.

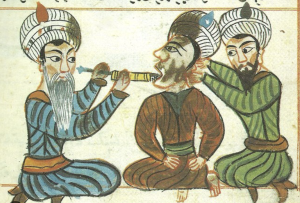

Towards the end of the first millennium, Arab physicians adopted a practice of seating patients on the floor for tooth removal (Figure 1, 2). In 1092, barbers, entrusted with various tasks by Pope Cyril the III of Alexandria, including hair cutting for monks, gradually expanded their services to encompass surgical tasks such as bleeding and tooth extractions. During this period, sitting on a chair became the expected position.

Figure 1. Arab physician extracting a tooth. Figure 2. Arab physician cauterizes a carious tooth using a protective cylinder to avoid burning the oral soft tissues. The patient is held down to keep him steady.

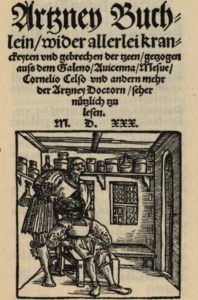

Depicted in the 1530 “Artzney Buchlein” (Figure 3a), a dental chair emerges as a carved wooden armchair with a high back, with the dentist standing behind the patient during tooth extraction. Additionally, a tooth-puller (Figure 3b) showcases a simple bench for a patient losing teeth, with a table nearby covered with extracted teeth. (Artzney Buchlein, 1530, Weiditz, 1531)

Figure 3. Dental chairs in the 16th century. 3a. Artzney Buchlein’s illustration of a tooth drawer with a patient seated in a carved wooden chair. 1530. 3b. The tooth-puller with a patient seated on a wooden bench. – woodcut – artist, Hans Weiditz II, c.1531.

In the 18th century, Mouton, Pfaff, French, and German dentists provided house calls for wealthy patients, repurposing home chairs as comfortable seats. In 1717, Laurence Heister, as well as Ludwig Cron, suggested different seating positions for tooth extraction, specifying floor seating for lower teeth and chair or bed seating for maxillary teeth, especially for pregnant patients (Figure 4) (Cron, 1717)

Figure 4. Proper positioning of the patient when extracting a lower tooth by a right-handed or left-handed dentist – according to Ludwig Cron, 1717. Illustrations on p. 187, 191.

Pierre Fauchard, in 1728, identified as a “chirurgiene dentiste,” described using a padded fauteuil or a low chair for dental procedures (Fauchard, 1728) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Fauteuil from c. 1750. Image from the Vienna Medical University, Museum of the History of Dentistry, reproduced with permission.

The first native-born American dentist, Josiah Flagg Jr. (1764-1816), is renowned for modifying a Windsor chair into one of the first custom-built dental chairs with a wide armrest and a wooden headrest (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A replica of the Wilson chair modified by Josiah Flagg Jr., without the headrest. The original is on display at Temple University School of Dentistry.

By 1831, James Snell adapted a chair to allow a reclining position (Figure 7). In 1841, J.C.F. Maury (1786?-1840?) presented a large fauteuil with a high back as the ideal dental chair.

Figure 7. James Snell – adjustable dental chair – 1831.

Over the next century, dental chairs evolved from wooden structures to padded ones with adjustable headrests, backs, and height. As dental treatments advanced, additional features such as spittoons, lights, trays for instruments, drills, water, air, and suction were incorporated.

S.S. White, the first dental supply company, opened in 1844 in Philadelphia, selling the first dental chair. In 1848, thanks to M. W. Hanchett, the chair gained a headrest and additional adjustable features. To accommodate itinerant dentists, a portable headrest attachable to any wooden chair with a high back was invented.

In 1851, T. C. Ball patented a hydraulic chair, and by 1855, a lifting jack was added for height adjustments. By 1870, spittoons became standard features.

In the 19th century, dental chairs underwent further modifications, including folding backs, lifting mechanisms, and increased comfort through soft padding.

Following the Industrial Revolution, the demand for dental services surged, leading to rapid innovation in dental office furniture. In 1869, James Beall Morrison introduced an adjustable iron-cast dental chair with a tilting back, forward and backward movement, and a lifting crank. Subsequent improvements included a foot pedal for height adjustments and chair rotation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Three models of dental chairs from the end of the 19th century and early 20th century. 8a. c. 1870 dental chair with spittoon attached to the side. Image from the Vienna Medical University, Museum of the History of Dentistry, reproduced with permission. 8b. 1879 E.T. Starr Dentist’s Chair – US Patent. 8c. Early 20th-century dental chair and stool. Image from the Vienna Medical University, Museum of the History of Dentistry, reproduced with permission.

Technological advancements in dentistry led to the invention of the saliva ejector, air dryer (blower), bracket table, and lamp. In 1917, the Ritter Co. added X-ray, suction, water jet, and cooling as integral components of dental unit (Figure 9).

Figure 9. A 1920 Ritter Dental Unit with the dates when integral components were patented.

The modern dental chair, resembling a reclining sofa with an aerodynamic design, was introduced by Dr. Sanford Golden and awarded a gold medal at the 1962 World Fair in Seattle. This design remains in use in most dental offices today.

References

Artzney Buchlein (1530). Artzney Buchlein wider allerleikranckeyten und gebrechen der zeen gezorgen aufs dem Galeno, Avicenna, Mesue, Cornelio Celso und andern mehr der zrtzney doctorn seher nütlich zu lesen. Michael Blum, Leyptzigk.

Cron, Ludwig. (1717). Der bey dem Ader-lassen und Zahn-ausziehen … recht qualificirte Candidatus Chirurgiæ oder Barbier-Geselle. Leipzig, Frederich Grosschuff. p.187, p.191.

Fauchard, Pierre (1728). Le Chirurgien Dentiste. Vol II. p.104 (using a regular armchair – fauteuil – for dental chair for extraction).

Weiditz, Hans (1495?-1536?) – Die Zahnbrecker, woodcut, c.1531. In Petrarch’s Trostspiegel in Glück und Unglück, Frankfurt am Main, 1584. https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/handle/10713/2443.

by Andrew I Spielman

In the nascent phase of dentistry, when tooth extraction reigned supreme as the primary therapeutic approach, most practitioners, known as tooth drawers, were nomadic. However, there were exceptions; in Ancient Rome, a well-established tooth drawer operated from a shop (taberna) in the marketplace. Notably, a 1987 excavation at the Temple of Castor and Pollux revealed 86 carious teeth in the drain pipe beneath the floor of a taberna, providing evidence of dental practices dating back to 50-110 CE. This taberna also served as a dispensary for pharmaceutical potions (Becker, 2014).

As the first millennium drew to close, Arab physicians conducted dental procedures in public spaces, utilizing marketplaces where practitioners and patients found spots organically. Furniture was unnecessary; patients either sat or kneeled before the standing or sitting practitioner (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Arab physician extracting a tooth. Note, the patient kneels while the standing practitioner extracts the tooth in a tent, probably in a marketplace.

The 16th-century dental office in Artzney Buchlein (Figure 2) and a 16th-century Dutch painting (Figure 3) both reveal compact spaces, around 100 sq. ft., dedicated to dentistry. These spaces typically featured a chair in the middle, often facing a window, with shelves displaying herbal potions used in dental treatments.

Figure 2. Dental office in the 16th century. Artzney Buchlein’s illustration of a tooth drawer with a patient seated in a wooden chair. 1530.

Figure 3. Dental office in the 17th century. Gerrit Dou, Dutch painter, The Extraction of Tooth, 1630-35, (Louvre, Paris).

Less-established tooth drawers, possibly with questionable reputations, roamed from place to place, as depicted in a 17th-century Jan Steen painting (Figure 4). In some instances, mountebanks, entertainers and sellers of secret potions often resorted to tooth drawing as well. Such activities would take place in marketplaces, surrounded by entertainment, with the main purpose of selling a product. In Paris, tooth drawers congregated on Pont Neuf (King, 1998).

Figure 4. Jan Steen, Dutch painter’s depiction of a public tooth extraction, 1650. Itinerant dentists either tied the patient’s arms to the chair or had volunteers hold the patient down while the tooth was yanked out.

Up until the early 18th century, itinerant tooth drawers provided “emergency services” with no follow-up, requiring minimal furniture such as a chair and a pair of forceps. Dentists either restrained patients by tying their arms to the chair (Figure 4) or relied on volunteers to hold patients down during extractions.

In the early days of the American colonies, dentists from England and France were esteemed as the best educated. They advertised their services upon arrival in a city, often renting empty stores for several weeks before moving to another city.

Here is the text of an advertisement taken out by one, James Mills, on January 6, 1735, in the New York Weekly Journal:

“ Teeth drawn and old broken stumps taken out very safely and with much care by James Mills, who was instructed in that art by the late James Reading, deceased, so fam’d for drawing teeth. He is to be spoke with at his shop in the house of the deceased near the Old Slip Market”

An advertisement from 1767 by Robert Wooffendale states:

“Lately arrived from London but last from New York, surgeon dentist (who was instructed by THOMAS BERDMORE, Esq; operator of the teeth to his Britannic Majesty) begs leave to inform the public, that he performs all operations upon the teeth, gums, sockets; also fixes artificial teeth so as to escape discerning, and without the least inconvenience”.

The 18th century marked a shift as dental interventions expanded beyond extractions. Established dentists began to have their own offices, with Vienna boasting four fixed-office dentists in 1783, Berlin listing two in 1786, and Paris flourishing with 30 dental experts, including two women, in 1761 (Figure 5). Pierre Fauchard was one of the experts. He had an office in Paris on rue des Cordeliers. (Dagen, 1926).

Figure 5. List of dental experts and Masters of Surgery in Paris in 1761. (from Dagen, 1926). Two on the list are women, Calais and Hervieux.

As demand for dental services increased, dentists stayed in cities longer, setting up shop in dedicated apartments. Offices required minimal furnishings, often multipurpose furniture and a bag with easily transportable instruments. John Greenwood, George Washington’s favorite dentist, exemplified this transient practice by having 19 different locations within a mile radius in New York over 33 years (1786-1819) due to the tradition of moving on May 1st.

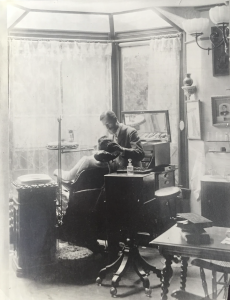

With the increasing complexity of dental treatments, the mid-19th century saw dentists carving out sections of their living rooms for makeshift offices (Figure 6). The shift from improvised settings to more formal offices aimed at separating personal and professional lives became evident, especially in the second half of the 20th century when private offices were established in designated office buildings, particularly in major cities.

Figure 6. The dental office of Dr. H.N. Dodges, in Morristown, NJ, 1886. Note the lack of electricity, street clothes, and practicing standing by the side of the patient. Dr. Dodges was a faculty member at the New York College of Dentistry. (Photo courtesy NYU College of Dentistry Historical Archives, reproduced with permission).

A notable evolution in dental offices in the second half of the 20th century was the establishment of group practices featuring multiple dental specialties. This model included endodontists, periodontists, prosthodontists, and oral surgeons. Other combinations also existed.

As regulatory burdens increased, some younger dentists opted for a different route, choosing to rent space in Dental Service Organization-run offices rather than buy and manage their practices. This allowed them to concentrate solely on treatment, although at the expense of ownership.

The early 21st century witnessed a surge in Dental Service Organizations (DSOs), with 34% of graduating seniors in 2023 considering joining a DSO instead of pursuing private ownership.

References

Artzney Buchlein (1530). Artzney Buchlein wider allerleikranckeyten und gebrechen der zeen gezorgen aufs dem Galeno, Avicenna, Mesue, Cornelio Celso und andern mehr der zrtzney doctorn seher nütlich zu lesen. Michael Blum, Leyptzigk.

Becker, M. J. (2014). Dentistry in Ancient Rome: Direct Evidence for Extractions Based on the Teeth from Excavations at the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum. International Journal of Anthropology, 29(4), 209-226.

Dagen, Georges. (1926). Documents pour servir à l’histoire de l’art dentaire en France : principalement à Paris. Editions de la Semaine Dentaire.

King, Roger (1998). The Making of a Dentiste. c 1650-1760. Ashgate, Aldershot, Brookfield USA, Singapore, Sydney.