by Andrew I Spielman

100 C.E. in a shop on the Roman Forum.

Imagine yourself in the year 100 C.E. in Rome, a common person of 18. The emperor is Trajan (98-117 C.E.), and the empire is about to be extended to its largest size with the conquest of Dacia, north of the Danube in 106 C.E. The Forum is a busy place, with small shops and stands for vendors, merchants, tradesmen. Among those, there is a stand dealing with teeth. If you have a toothache, this may be the place to visit after the head of your household exhausted herbal remedies to ease your toothache.

As you walk the open stands of the Forum, near the Temple of Castor and Pollux, you come upon this one that is told to be skillful in removing teeth. He asks you to sit on a stone chair in the open air. He looks into your mouth and quickly finds the deeply carious tooth on your lower jaw. He takes resin mixed with the stingray’s bone, pastinaca, places it inside the tooth and around it to soften the bone and asks you to return in a week. When you are back, he takes wood fiber and lint and fills the tooth to avoid fracturing it during extraction. As you sit, the tooth drawer’s helper holds your head firmly. There is no anesthesia, running water, or even hand washing. The tooth drawer places his index and thumb around the tooth and gently rocks it as it becomes increasingly mobile. You feel the pain and are restless, but the helper’s firm hand prevents you from moving. After a few minutes, the tooth is gently removed in its entirety. No forceps are needed. The tooth is dumped onto the floor and washed away with a water pitcher. The tooth disappears into the sewer under the shop floor and into the cloaca maxima. Before you depart, you pay eight sestertii for the service. It is less than the cost of a top-shelf wine and half that of a new tunic. As you depart, the tooth drawer makes a few recommendations to clean your mouth. He suggests wiping your teeth with a woolen cloth dipped in honey and crushed oysters, salt and soot, gargling in the morning with water, and hyoscyamus fumigation for tooth worms. Your pain eases, and you are happy the tooth is gone.

1000 C.E. in a shop on the market in Cordova, Al Andalus.

Cordoba, in 1000, is a city of 100,000 inhabitants, one of the largest and most important cultural centers of Europe, and the capital of the Umayyad Dynasty ruled Al Andalus.

You are a middle-aged person with a deep cavity and a spontaneously painful tooth. You are walking the market along the Guadalquivir River, near the Great Mosque.

The busy market has a few shops, but you are looking for one that says daraj al’asnan (tooth drawer), where you can find someone caring for your tooth. You walk into the shop. It is rather dark, with a few oil lamps providing light. The keeper has shelves with large jars filled with herbal medicine and a few large manuscripts. To the side, an open fire pit with a cauldron of boiling oil and several irons kept in the fire. You are seated on the floor in the middle of the room with one helper standing behind you and holding your head and the tooth drawer kneeling in front of you. He had already identified the tooth that causes the problem and decided to cauterize it with a hot iron. He removes a long hollow tube and inserts the hot cauterizing instrument into the affected tooth. The tube is meant to protect your cheek from getting burnt. He scrapes the bottom of the cavity with the sharp, hot instrument and inserts the sharp end into the open pulp, cauterizing the painful tooth. He could have used a few drops of acid to achieve the same. With the nerve necrotized, the pain gradually subsides.

1500 in a barber-surgeon’s shop in London

bleeding or through leeches.

You are a person of some means and seek the services of a barber-surgeon. You have a terrible toothache and cannot eat. You visit the barber-surgeon in his shop close to the Tower of London, at the city’s edge in 1500. London is a city of 60,000 people. England has three more towns, Norwich, Bristol, and Newcastle , with populations exceeding 10,000. The king of England is Henry VII.

Outside the shop of the chirurgeon (surgeon), a striped blue and white pole indicated the nature of the shop. In addition, a gallipot and a red flag are also displayed, indicating this is no simple barber. The shop is one large room with windows and 6-8 chairs, several washing basins, a desk, and shelves. You are seated in a wooden chair with a high back. You look around. Large metal plates are hanging on the wall. They are used for bleeding, a common practice in that period. Bloody bandages used in previous cases are washed, set to dry, and dangled in the wind. They will be reused. All kinds of metal tools are hanging in the wood-paneled room. These are instruments for the variety of procedures the barber-surgeon is doing. There is a large desk with a few books on it. You cannot read; only clergy and nobility members could, but if you could, it would say Guido de Cauliaco (Guy de Chauliac) – Chirurgia Magna. It has been the standard source of surgery for at least 150 years. The large room has other clients; some are bled from their arms to rebalance their bad humors. One individual is getting a leg amputated with a large saw. Two helpers are holding the man down. His arms and body are strapped to the chair. There is an outcry as the surgeon quickly amputates the leg, followed by cauterization of the blood with a hot iron. There is no painkiller, but his most critical skill is quickness. Your tooth extraction seems trivial compared to the pain of amputation. The surgeon identifies your tooth and picks up a hook-cramp, a pelican, and a forceps, all instruments redesigned by Guy de Chauliac, the famous surgeon from Montpellier. The surgeon grabs the tooth with the hook-cramp and yanks the tooth. The tooth cracks and breaks at the gum line. It does not matter; most of the tooth is out. You are happy the pain subsides in a few days, and can eat again.

1750 in a dentist’s office in Paris

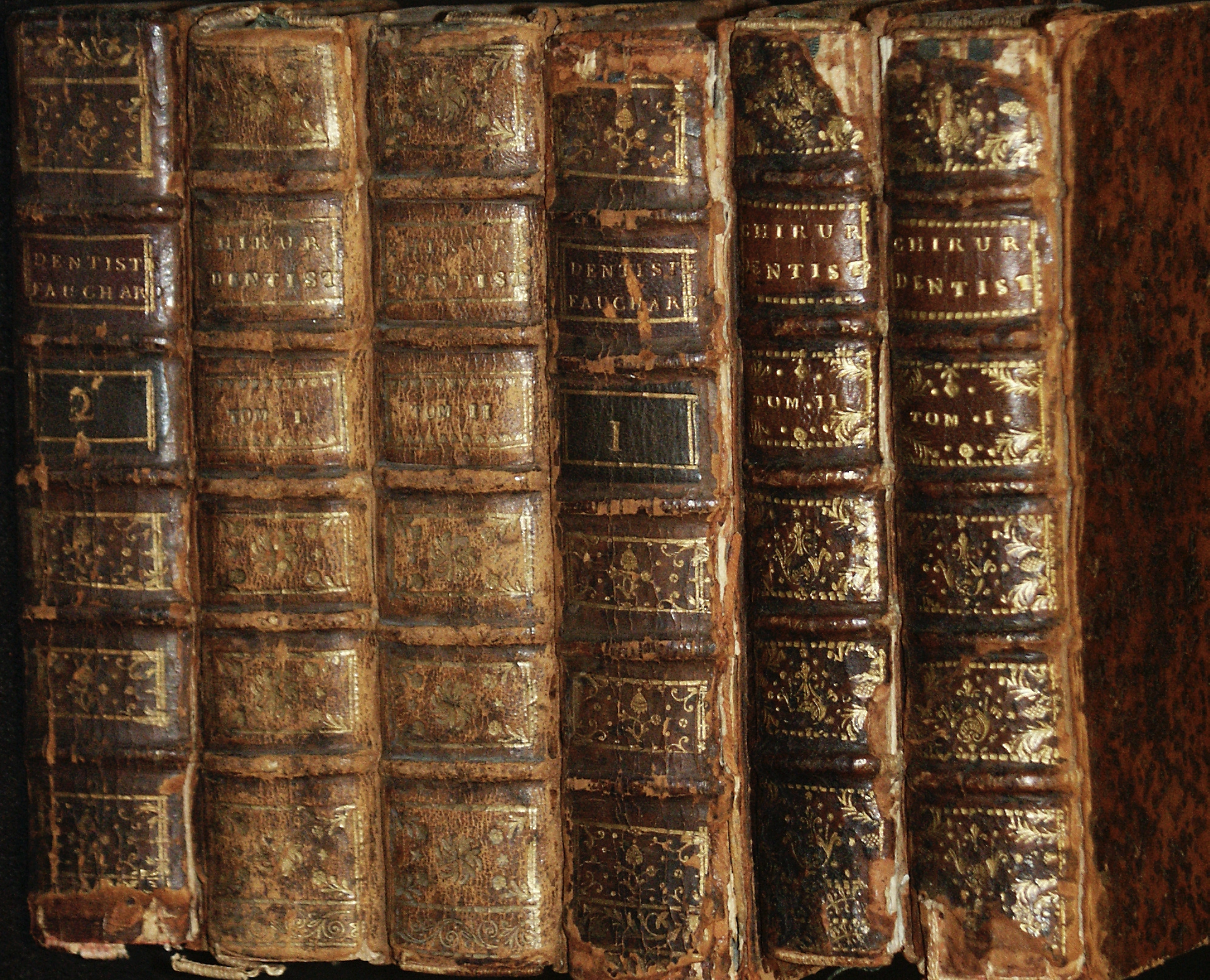

dentist in the middle of the 18th century Paris

The chirurgien-dentiste just finished his 3-hour exam on surgical principles, blood-letting, cupping, herbal medicine, wound surgery, abscesses, and extractions. The committee included three individuals, including the Premier chirurgien, or the first surgeon of the king, a powerful position. To prepare for the exam, the surgeon used a text of Guy de Chauliac – Le Maistre en Chirurgie from 1740, edited by Laurence Verduc. He had to memorize every line of this 560-page abbreviated text of the famous Montpellier surgeon. Guy de Chauliac’s book has been the staple of every surgeon for close to 300 years. Passing the exam earned him the title of expert pour les dents. He set up shop in the heart of Paris, with about 600,000 inhabitants. Several famous colleagues have stolen the spotlight: Pierre Fauchard published the second edition of his Le Chirurgien Dentiste. Claude Mouton published a textbook on artificial teeth, the latest rage in the French capital.

You seek out this chirurgien-dentist for a comprehensive problem: several large carious lesions on your teeth, tartar, and some missing upper teeth. After all, there is a new dawn in resolving dental problems, not just extracting them. His office is spacious and elegant. You are seated in a fauteuil in front of a large window to get enough light and be examined. The Chirurgie-dentiste has a new tool for examination, a small oval mirror with a long slender handle and a sharp probe. After some discussions, it is decided to try to save the teeth using the latest developments: remove some of the dark substance at the bottom of the cavity, scraping it away, filing down some sharp edges of the teeth, and using molten lead, to fill the teeth. The tartar deposits on the lower teeth are scrapped away with newly designed sharp instruments. The recommendation is to gargle daily with fresh urine to reduce decay. The surgeon just read about it in the famous Pierre Fauchard’s book published in 1746.

As for the missing posterior upper teeth, there is a brand new spring-supported upper denture with two carved ivory blocks to fill the missing posterior space, connected with a metal bar. Eating with them is out of the question, but they provide at least the appearance of a mouth filled with teeth.

1800 in a dentist’s office in Dresden

Dresden had 60,000 inhabitants in 1800 and was the largest royal city of the Dutchy of Saxony. You are an elderly patient in need of major dental treatment. You have lost all of your upper teeth and had given up on having teeth until you heard about this dentist in Dresden. His office is in the Old Town, close to the bridge on the Elba, on a busy street. You walk into the elegant townhouse. The waiting room is spacious. You are shown into the office and seated on a chair. The room has large windows facing west to provide enough light. The room looks like a study, with many books lining the shelves.

Some titles are in Latin; others are in French, German, and even English. The dentist, dressed in elegant street cloth, looks carefully into your mouth. You both agree on the treatment to make you a denture. There is a new technique to ensure a good fit. Unlike previous techniques where the dentist carved the denture out of a block of ivory with a rather poor fit, he takes a small tray, fills it with softened beeswax, and takes an impression of the edentulous surface. He also takes an impression of the opposite jaw to ensure a good match. The wax impressions are poured up in plaster and articulated together to match the situation in the mouth. The denture base is a gold plate fitted onto the plaster mold. You have a choice: a selection of human teeth, procured from people who sold them, cut at the gum line and riveted to the brass plate, or a new French invention, teeth made of “mineral paste”. The denture will be supported by springs against a lower partial denture frame. This work is state of the art for 1800, with advances from France, America, and Prussia incorporated.

1850 in a dentist’s office in Philadelphia

You are a well-to-do merchant in the city of Philadelphia in 1850. The city is the second largest, after New York, with over 500,000 inhabitants. Your dentist has an office downtown, close to Liberty Hall. The dentist has real qualifications; unlike the other 550 dentists in the city, you obtained your diploma from the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. Many dentists just apprenticed with other dentists before putting up a sign. There are plans to open a dental school in Philadelphia in the next two years.

You need restorative work for several decayed teeth. Your diet has changed as you could afford more expensive foods and now includes imported chocolates from Belgium. You noticed a rapid deterioration of your teeth. You walk into the dentist’s office, a large spacious room. There is a special leather chair with armrests, a headrest, a partially adjustable back, a foot rest and even a crank to lift the chair. Next to the chair, a large spittoon is visible. A large tray holds instruments neatly arranged. The handles are beautifully decorated. This is the dentist’s only set of instruments, which are reused for every patient. He even has a small bow drill to help clean the cavity. He will place a new filling material, cement, a German invention. There were other options to fill the teeth, like amalgam, but it was recently banned in America since two Englishmen named Crawcours used it. There is some talk about lifting the ban.

The dentist also noticed a root that needed removal. You balk at the idea because there is like pain involved. He assures you he can make the pain disappear using the newly introduced laughing gas (nitrous oxide) anesthesia. The dentist produces a leather bag and lets you breathe in. Although you are conscious and feel giddy, you do not feel any pain as the dentist removes the root with root forceps. This specially designed instrument came from England and was designed recently by a fellow named John Tomes.

1900 in a dentist’s office in Vienna

You are a civil servant in the Imperial court of Franz Joseph. You need complex dental work. Your dentist has graduated from the Medizinischen Universität Wien, the medical school. In Vienna, dentists first graduate from medical school and specialize in dentistry. Vienna is the medical capital of the world. Part-time dentist practices in the Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien. It is a prestigious position. In his private office on Kärntner Strasse in the heart of Vienna, you are led by a servant to a waiting room. When you are finally seen, the office appears like a comfortable study with books lining the shelves and, in a corner, a large leather chair, fully adjustable headrest, back, footrest, and a hydraulic pump to adjust chair height. A unit is next to the chair fitted with a saliva ejector, a tray to hold instruments, a cup to rinse your mouth, a cuspidor, and a chord-driven engine attached to the unit. A foot pedal operates the drill. This office will soon be connected to the electric grid and get running water. So far, only 3% of households in Vienna are connected.

Your dentist carefully examines your mouth and decides you need a new upper dentures. The old, spring held, gold-plate denture is no longer comfortable and has become quite loose. There is a new invention straight from America that uses Vulcanite, a black rubbery substance obtained from hardening the resin of the rubber tree, which is far better fitting. Artificial teeth will be made from porcelain. One can even select the right color and shade.

As for restorative work, the dentist uses the foot-pedal operated drill to clean the cavity. The tooth is sensitive. He places some zinc-oxide eugenol to smooth the pain. For other teeth in the back, he is placing amalgam fillings. The assistant mixes the silver shavings in a mortar with a drop of mercury. She mixes the two using a small mortar and pestle until he gets a paste consistency. To remove the excess mercury, he uses a piece of leather. Once squeezed, the amalgam is the right consistency to place it into the cavity. The excess mercury is thrown into the garbage. For a broken down tooth, there is no hope for simple restoration. He is planning to place a gold jacket crown. You are very satisfied with the service you are getting. The bill sent to your home will reflect a steep price for the service.

1950 in a dental office in Toronto

With our current knowledge and technology, it is hard to imagine what was like being treated in 1950. It is easier to state what was and what was not available.

Your dentist, a graduate of the University of Toronto, Faculty of Dentistry, is an excellent, careful, but conservative professional in treatment. He graduated at the top of his class in 1930 and has his diplomas on his office wall. He even specialized in prosthodontics, a specialty recently declared for those making crowns, bridges, and dentures. Nevertheless, he is permitted to see patients with general concerns. His office is a bit dated, perhaps from 1930, but he is up to speed on all the techniques. Your dental needs require some drilling and filling. Drilling is done with a cord-driven motor attached to the unit. It can reach up to 25,000 rotations per minute. Although not painful, you request a local anesthetic. A new anesthetic, lidocaine, became available just a few years ago. It does not cause any allergies, unlike novocaine. The office has running water and electricity; the electric drill is managed with a foot pedal. There is suction and air/water attached to the unit. The cavity is first filled with a cement liner and white silicate cement to match the other front teeth.

As far as your missing teeth are concerned, you will be fitted with a partial denture made of plastic material acrylic. It has been on the market for 12 years and is far superior to Vulcanite. The denture should last for at least 8-10 years.

2000 in a dental office in New York

The dental office offered all the amenities at the start of the 21st century. If one could have been transported from 1950 into a dental office in 2000, one could hardly believe the transformation. Gone is the cord-driven low-speed drill. Since 1957 it was replaced with a high-speed drill, cooled with a jet of water. One sits comfortably in a fully reclining chair. The smell of the zinc oxide eugenol, the staple of the 1950s, is gone. Instead, several non-odorous, esthetic choices are available. Dental office exudes safety, competency, esthetics, painless intervention, and a wide range of choices. Many patients now grow up without a single dental restoration or loss of a tooth. Fluoride turned out to be a good agent to prevent dental decay. As a result, most of the major city water supplies are now fluoridated. Implants became a fundamental staple of dental choices. They now outlast crown, bridge, and endodontically-treated teeth. Porcelain laminates and composite resins since the mid-1950s can provide esthetic solutions which are hard to distinguish from the natural tooth. We can now design crowns on a computer and visualize them beforehand. Computers are everywhere, and much of the work is digitized, including X-rays. The internet provides information to patients, and they can educate themselves.

Since the late 1980s, when the AIDS epidemic hit the world, dentists have been wearing gloves, masks and face shields, headlamps, and magnifying glasses. They are even trained to check for the presence of oral cancer. Dental anesthesia is sophisticated, with topical anesthetics to blunt the needle’s prick and atraumatic thin needles to inject effective anesthetics. Children can get sealants, varnish, and fluoride trays to prevent dental decay. Some countries (not the US) have introduced a new professional, a dental therapist, to provide preventive work.

2050 in a virtual office ……

Students graduating in the next few years with a 25-year practice will likely check the predictions listed here.

Picture yourself as a 50-year-old individual living in 2050, seeking dental care for neglected teeth and gums. In need of professional attention, you opt for a virtual consultation with an oral specialist, conducted from the comfort of your living room while the specialist operates remotely from their office.

Using smartphone attachments, you provide a comprehensive view of your oral health, including saliva, oral tissue, and bacteria samples. Through advanced technology, each tooth and its supporting bone level are assessed without requiring X-rays. A virtual chart detailing your oral cavity is generated, integrating with your extensive personal data stored in a vast database encompassing your microbiome, genome, proteome, sociome, and connectome. A virtual chart and survey of your oral cavity are created.

Utilizing artificial intelligence, a tailored treatment plan is devised, addressing various risk factors and suggesting improvements across physical, microbiological, oral, dietary, and social domains. In the case of damaged teeth, the option to regrow a new tooth is presented. By providing a cheek epithelium sample, a specialized service grows a specific tooth, such as a lower second bicuspid, in a Petri dish.

In three months, a surgical appointment is scheduled with an oral surgical specialist. The damaged tooth is extracted, and the custom-grown tooth bud is implanted into the socket. With the aid of growth factor stimulants, the new tooth gradually emerges in place over the following months, accompanied by minor orthodontic adjustments to ensure proper alignment.

Alternatively, expedited services offer the option of 3D printing a tooth based on your stem cells, significantly reducing the wait time compared to growing a tooth bud from scratch.

Copyright 2022 © HistoryofDentistryandMedicine.com