by Andrew I Spielman

How to cite this paper: Spielman, AI. History of Dental Education. In: Illustrated Encyclopedia of the History of Dentistry, 2023. https://historyofdentistryandmedicine.com/

The earliest form of dental education was an apprenticeship. Apprenticeship appeared with the earliest dental interventions, which dates 13,000 years back from the Late Upper Paleolithic in Tuscany, Italy (1). Evidence from the Neolithic period, 7,500-9,000 years ago, from Pakistani graveyards showed the effective use of drills to remove decayed tissue from teeth (2). The first sign of the restoration of tooth decay appeared in a 6,500-year-old specimen found in Slovenia, where beeswax was used, presumably to restore a cracked tooth (3). These interventions were associated with anonymous practitioners, and their knowledge was passed on to others based on observation.

The first dental practitioner whose name is known was Hesy Ra, an Egyptian employed by King Djoser, a 3d millennium BCE pharaoh. He was coined “the great one of the dentists”.

A Sumerian clay tablet with a cuneiform inscription dating to 3,000 BCE refers to the legend of the “tooth worm” that is thought to cause tooth decay. This was the earliest written record related to teeth.

The first “textbook” is the Edwin Smith Papyrus, which includes treatment for head and neck trauma, a 4.68 m scroll from the 16th century BCE. The level of sophistication depicted by the Edwin Smith Papyrus far exceeds Hippocrates’ knowledge a millennium later.

Until the 16th century, no text was exclusively dedicated to the oral cavity or teeth. Instead, medical texts by physicians such as Galenos of Pergamum (130-210) or Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (980-1037) included some references to how to treat oral and dental conditions. The first book dedicated exclusively to teeth, Zene Artzney (Medicine for the Teeth) (4), was published in Leipzig in 1530. The German text targeted itinerant dentists and provided advice on loose, decayed, or painful teeth. In 1543, the first atlas and text, perhaps the most important medical text, was published. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua, published, De humanis corporis fabrica (On the workings of the human body) (5), a scientifically more accurate and artistically extraordinary atlas and text. Twenty years later, Bartolomeo Eustachio (1510? -1574), published the first comprehensive work on teeth entitled Libellus de dentibus (A treatise on the teeth) (6-7).

The next step in the evolution of dental education is the emergence of a prominent practitioner with published works. The first to do so was Ambroise Paré, a barber-surgeon to four French Kings, and a practicing dentist who dedicated three chapters to dentistry (Chapters VIII-X) in his Oeuvres (Works, 1575). It includes treatment of mandibular subluxation, traumas to the tongue, and description of instruments used by the barber-surgeons (8-9). Paré accumulated his experience during the Italian and French Wars of Religion, where he perfected the cauterization of caries and re-implantation of teeth.

The textbooks facilitated the dissemination of knowledge and supplemented observation or a formal apprenticeship. In the profession’s early days, training and practicing were unregulated and virtually unrestricted. That led to a range of individuals assuming the practice, some completely unqualified. Practicing dentistry was not a full-time profession until formally regulated. However, both barbers and surgeons claimed to be the torchbearer of the profession. They performed various tasks, including extractions, blood-letting, shaving, and cutting hair or even limbs, thus assuming the role of barber-surgeon. Simple barber surgeons moved from town to town, performing their craft in public spaces. Those that proved more skillful became employed in the service of wealthy protectors, forgoing the itinerant lifestyle. Endowed with a fixed place, their craft was passed on to their descendants or students (for a fee) in search of apprenticeship for a period usually not exceeding 1-3 years.

The turning point in dentistry occurred in 1728 with the publication of a comprehensive overview of dentistry by Pierre Fauchard, Le Chirurgien Dentist (The dental surgeon). (10)The work marked the beginning of dentistry as a specialized profession. As a result, Fauchard is rightfully considered the “father of dentistry”.

While apprenticeship was necessary to practice, requiring a formal license was the next step. In 1771 Benjamin Fritsche, a Mecklenburg dentist, got permission from the faculty of medicine at Christian Albrecht University in Kiel to formally practice dentistry. Hiring dentists to teach medical students or medical personnel to train dentists was the next step in the evolution of dental education. In an advertisement in 1787 in the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertisement, Dr. Foulke announced five lectures in medical subjects that would “enable Country Practitioners to become useful experts Dentists” (11). Formal lectures on dentistry to medical students were first given in 1799 at Guy’s Hospital in London. The teacher was Joseph Fox, author of the 1803 volume on “The Natural History of the Human Teeth”, a student of John Hunter. Guy’s Hospital was the first to appoint a dental surgeon to its staff (12).

A less-known fact is the January 4, 1816 initiative of the Faculty of Medicine in Paris to establish a chair of Dental Medicine. The chair of the new unit would have been C. Fr. Delabarre, a noted Parisian dentist and author. However, the Ministry of the Interior, responsible for academic matters, rejected the initiative. (13).

In what we call today the dental school, these modest steps presaged the era of concurrent education of multiple dental students in a formal setting. The next step was the opening of dental schools. Still, such institutions provided educational opportunities to enter the profession but not life-long learning to keep up with the growing body of knowledge. That was where professional publications and professional societies played a significant role.

Horace Hayden (1769-1844) and Chapin Harris (1806-1860) emerged in the US during the first part of the 19th century as the leaders of a movement to change dental education. They saw the need to extend dental education to medical students to elevate the status of dentistry. Along with Eleazar Parmly, they saw a four-step approach to enhance the profession of dentistry: 1. establish dental departments within medical schools; 2. establish professional publications to provide a forum for sharing knowledge, 3. set up professional societies where dentists could meet regularly, and 4. establish legislation to regulate the practice of dentistry.

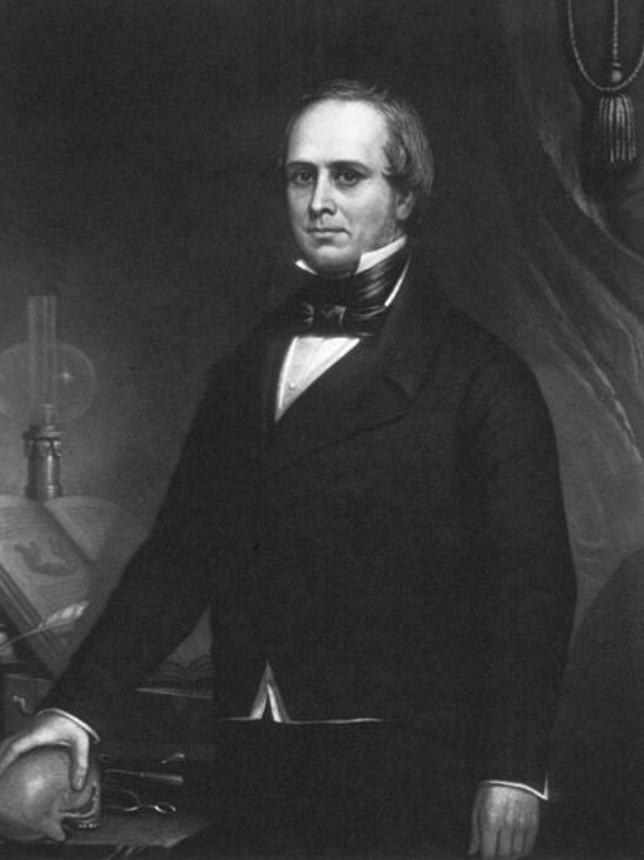

Horace H. Hayden (1769-1844)

Chapin Harris (1806-1860)

Horace Hayden used John Hunter’s book, The Natural History of the Human Teeth, to self-educate. That was followed by an apprenticeship with John Greenwood, one of George Washington’s dentists. Hayden opened his practice and secured the respect of educators from the University of Maryland Medical School. In 1837, he was invited to give a course in dentistry to medical students at the University of Maryland. Chapin Harrisfirst studied medicine and practiced in Greenfield, Ohio, with a focus on dentistry. After he attended his brother John’s Bainbridge, OH, private training, Chapin settled in Bloomfield, Ohio, where he practiced medicine, surgery, and dentistry.

In 1837 Hayden and Harris approached the University of Maryland administration with a request to establish a Dental Department with a full course in dental training as part of the medical school. Their request was denied. Consequently, in 1839, they petitioned the Maryland Legislature to establish an independent dental school. Despite opposition and lobbying from the medical establishment, their charter was granted on February 1, 1840. Later that year, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, with four professors, the first dental school in the world, was opened. The requirement for graduation was either completion of two sessions or two years of preceptorship. Each session lasted no less than four months, but the facilities were inadequate. Not until 1846 was the first practical instruction in a dental infirmary added to the curriculum. Horace Hayden became the first president of the dental college and remained in that post until his untimely death in 1844, after which Harris took over the position.

Dental education in Europe had a different path. In 1845 John Tomes (1815-1895) gave a series of lectures to medical students at Middlesex Hospital. In 1856 under his leadership, the Odontological Society of London was formed. Two years later, the Odontological Society created a Dental Hospital (later renamed Royal Dental Hospital) in Soho Square. In 1859 the first dental school in the UK, the London School of Dental Surgery, opened. Other dental hospitals soon opened, including one in 1861, the National Dental Hospital (14).

In Paris, in 1834, Joseph Jean-Francois Lemaire (1782-1834), a physician that specialized in dentistry, author of Traite sur les dents (1820),and dentist to the King of Bavaria, offered a theoretical and practical course in dentistry at the University of Paris. He charged a fee of 10 francs11. The first formal dental school in Paris (École dentaire) opened in 1879, while in Canada, similar to the British dental schools, the University of Toronto was established in 1858.

In 1839, Hayden and Harris established the firstprofessional publication, The American Journal of Dental Science. In 1840, the journal had 317 subscribers from twenty-two US states and foreign countries, including England, Scotland, France, Holland, and the West Indies. The journal sparked a trend that continued with other trade publications, such as The New York Dental Recorder (1847), The British Journal of Dental Sciences in 1856, and the Dental Cosmos in 1859. At the same time, on August 18, 1840, in New York, Hayden, Harris, and forty of the brightest dentists of the time co-founded the American Society of Dental Surgeons. Harris was elected as its first president. It was a precursor to the American Dental Association (ADA), a name that was assumed in 1859. The Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario was created in 1868, and twelve years later, the British Dental Association followed in 1880.

During the mid-19th century, several attempts were to enact legislation to regulate the profession in the US. One of the earliest examples of this was in Alabama. On December 31st, 1841, the Alabama State Legislature passed an act regulating the practice of dental surgery. (15) The law, in effect, mandated that anyone wishing to become a dentist must be first licensed as a physician and must be approved by the medical board to practice. In 1868, New York, Kentucky, and Ohio became the next three states in the U.S. to enact legislation limiting the practice of dentistry. There was a minimum age limit of 16 and a minimum number of years of apprenticeship with a dentist, four years. Those meeting the criteria were entitled to an examination by the State Board of Censors.

In the UK, in the early 19th century, there was no control over who could practice unless one practiced in London or a seven-mile radius outside of it. In the City of London, the College of Surgeons and Physicians set specific rules for practicing. The Dentists Act of 1878 regulated the practice of dentistry in the UK. Limiting the practice of dentistry was an important step in controlling the widespread abuse by less-than-qualified individuals. However, the opening and running of dental schools were still unregulated. With few exceptions, early dental schools were for-profit trade schools. Curriculum and educators were not standardized. Dental education needs to mature and be reformed.

Following the example of Baltimore College of Dentistry in the following years, many other schools were established, primarily in the US. However, many early schools folded, merged, or were absorbed into other dental schools. Criticism of dental curricula in the US led to some improvements in educational requirements and length of education. The ADA established a minimum of two years for the course of instruction of a dentist. Despite such advances, uneducated dentists far outnumbered those that graduated from dental school. In 1860 in the US, only 9.5% of the practicing dentists had formal dental school training.

Overall, twenty-four dental schools opened in the US during the forty years from 1840-1880, all but five as proprietary and independent. European schools followed suit with London, Glasgow, Toronto, Montreal, etc. A handful of schools, starting with Harvard in 1867 and then Michigan in 1875 and the University of Pennsylvania in 1878, established dental departments as part of a medical school in a major university. As dental education formally took off, most institutions initially had two-session programs. The length of dental education increased to 3 and 4 sessions over the subsequent decades.

A critical juncture in dental education occurred when the Carnegie Foundation tasked William J. Gies, a biochemist from Columbia University, to review the status of dental education(16). Their report, published in 1926, was a seminal moment in the history of dental education. Mirroring the 1910 Flexner Report on the poor state of affairs of Medical Education (17), the Gies Report, as it became known, found a need to better cooperate between dentistry and medicine, to include in its curriculum findings of dental research, to include the basic sciences and to meet the demands for health care in the future.

The Gies Report was critical of the lack of science and standardization in dental education and set the stage for dental reform, an extension of the curriculum, the inclusion of basic sciences, and formal nationwide board examinations that appeared in 1934.

William J Gies’ influence was also felt in other ways. In 1919 Gies and an editorial board initiated the Journal of Dental Research. At the same time, he formalized a society, the American Association of Dental Schools, later called American Dental Educators Association (ADEA), a leading international institution that influenced dental education in the following decades.

In the close to a century since the Gies Report was published, dental education has expanded in its sophistication, prerequisites, scope, content, and requirements, yet again, it was challenged. In 1995, the Institute of Medicine issued a report entitled Dental Education at the Crossroads. Challenges and Change (18). In it, some of the challenges were to ensure that Oral health is part of total health, prevention rather than treatment of disease is the focus, and that all intervention is outcome-based; dental education does not end at the end of dental school: there must be life-long learning; to name a few.

Today dentistry is a highly regulated profession. There are nearly 2000 dental schools worldwide, not to mention dental therapy, dental nursing, and dental hygiene educational programs. The explosion of knowledge and the type of treatment one delivers is constantly changing. So is dental education. However, dental education will be truly at a crossroads in the next decades. A recent report on the Advancing Dental Education in the 21st Century challenged the profession to meet the demands of the next 25 years. In their word: Dental and allied dental education are now challenged by a new set of issues related to financing education, improved oral health, more effective treatment technologies, and a rapidly changing delivery system (19).

Technological advances in information delivery (virtual, simulation, or online), and scientific advances that make dental practice less invasive, ultimately, more accessible to laypersons will impact the format, content, timing, and location of education delivery. During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, some technological methods were displayed when most dental education had to move on-line for a while. Together, these will alter the way we interact with students and patients. Ultimately this will benefit society in general and the oral health status of patients in particular.

- 1. Oxilia

- 2. Coppa

- 3. Bernardi

- 4. Zene Artzney

- 5. Vesalius

- 6. Eustachio

- 7. Shklar

- 8. Pare (a)

- 9. Pare (b)

- 10. Fauchard

- 11. Foulke

- 12. Gelbier

- 13. Prevost p.50

- 14. Manuel

- 15. Clark p.277

- 16. Gies

- 17. Flexner

- 18. IOM Report

- 19. Bailit

References and notes on dental education

Bailit, Howard L and Farmicola, Allan J (2017). Advancing Dental Education in the 21st Century. J. Dent. Edu. 1004-1007.

Bernardini, Federico; Tuniz, Claudio, et al. (2012). Beeswax as Dental Filling on a Neolithic Human Tooth. PLoS ONE, Vol. 7, #9, p. e44904. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044904.

Clark, C.J. (1843). Letter from Dr. C.J. Clark, M.D. Secretary, Alabama, Medical Board. Am J. Dent. Sci. III(4):277-278. (Letter includes the wording of the 1841 Alabama Legislature regulating dentistry practice).

Coppa, Alfredo; Bandioli, Luca, et al. (2006). Paleontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry. Nature, Vol. 440, #7085, p. 755-6. DOI: 10.1038/440755a.

Eustachio, Bartholomeo (1563). De Libellus Dentibus. p. 1-96. (https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=LtdQAAAAcAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP1).

Fauchard, Pierre (1728) – Le Chirurgien Dentist. Two volumes. http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/histoire/medica/resultats/index.php?cote=31332×01&do=chapitre

Flexner, Abraham. Medical education in the United States and Canada: a report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York, 1910, p. 346.

Foulke (Dr.) (1787). Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Vol. XIV, Issue 85, October 23rd. (First advertisement by a medical practitioner to provide 5 lectures in medicine to become a competent dental practitioner.) American Antiquarian Society: https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=Maryland%20Journal%20and%20Baltimore%20Advertiser%2C%20Dr.%20Foulke&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=1787%20-%201787&docref=image/v2%3A108D68C94D87BEC0%40EANX-10FA09194892A808%402374044-10FA0919DE9E5160%400-10FA091AA2F3B160%40Advertisement&firsthit=yes)

Gelbier, Stanley (2016). Origins of dental education and training in the USA and UK. J. Hist Dent. Vol. 64, #3, p. 112-120.

Gies, William, J. Dental education in the United States and Canada; a report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, New York, 1926. p. 692.

Institute of Medicine (IOM) (US) Committee on the Future of Dental Education. (1995). Dental Education at the Crossroads. Challenges and Change, Field Marilyn, J (ed). (1995) National Academies Press. DOI: 10.17226/4925

Manuel, Diana E. (2009). Dental Education in Paris in the 1830s. Dental History, 2009, Jan. #49, p. 4-15.

Oxilia, Gregorio; Fiorillo, Flavia, et al. (2017). The dawn of dentistry in the late upper Paleolithic: An early case of pathological intervention at Riparo Fredian. Am J. Physical Anthropology Vol. 163, #3. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.23

Paré, Ambroise (a) (1583). Ouvres. Chapter XXV – Les instruments propres pour archer et rompre les dents (The instruments appropriate to pull and break up teeth), p. 513-516. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k53757m/f488.item.r=bouche

Paré, Ambroise (b) (1583). Ouvres. Chapter VIII-X – Cure particuliere des luxations: Et premierement de la Mandibule inferieure (Chapter VIII), Maniere de reduire la mandibule luxeé en la partie anterieure des deux costez (Chapter IX) and Maniere de reduire la mandibule luxeé seulment d’un costé. (Chapter X), p. 463-465. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k53757m/f488.item.r=bouche

Prevost, A. (1900). La Faculté de médecine de Paris, ses chaires, ses annexes et son personnel enseignant de 1790 à 1900. Paris, Maloine A., p.50, https://archive.org/details/BIUSante_52170/page/n53/mode/1up.

Robinson, Ben J. (1959). The American Association of Dental Examiners. JADA, 58(7):150-157. (The dates when individual state dental practice acts were established.)

Shklar, Gerlad and Chernin, David (2000). Eustachio and “Libellus de dentibus” the first book devoted to the structure and function of the teeth. J.Hist. Dent. 48(1):25-30.

Vesalius, Andreas (1543). De Humanis Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. Basel. Chapter I, Page 45 (https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/pageview/6299094).

Zene Artzney (1981). – The Classics of Dentistry Library, Birmingham, Alabama, Leslie B. Adam Publisher, p.133.

Zene Artzney (1541). (Medicine for the Teeth). Christoff Egenolff, 5th ed. Frankfurt am Main, p.48.

Copyright 2022 © Spielman – HistoryofDentistryandMedicine.com