History of the toothpick, dentifrice-toothpaste, mouthwash, toothbrush, dental floss and tongue scraper.

by Andrew I Spielman

How to cite this paper: Spielman, AI. History of Oral Hygiene Tools. In: Illustrated Encyclopedia of the History of Dentistry, 2023. https://historyofdentistryandmedicine.com/

If one walks through the painting galleries of medieval masters one feature strikes the viewer looking at human portraits: nobody smiles. Unless depicting a simpleton or the village idiot, every portrait shows a somber individual with pursed lips, without showing teeth. Victorians thought of smiling as obscene, inappropriate (1), nor did they have nice teeth to show for. The oral hygiene habits of yesteryears were so deplorable that foul looking and smelling decaying teeth were the norm. When Elisabeth I, Queen of England developed a “sweet tooth” for sugar, a newly imported luxury from South America, her teeth could not be saved. He blackened and broken down front teeth were a source of shame for her, to the point of banning any portrait to show her smile. She, apparently even covered the mirrors in her palace to avoid facing reality. Some of her courtiers, out of loyalty, painted their own teeth black, much like Ohaguro, the Japanese custom of dyeing one’s teeth black fashionable until the end of the Meiji period.

Up until medieval times, oral hygiene was neither systematically practiced, clearly understood, encouraged, nor a subject to write about. Occasionally we see Ancient Indian texts or Greek and Roman authors suggest one rinse one’s mouth to preserve teeth. The first to promote oral hygiene was Walter Hermann Ryff, a German surgeon from Strasbourg, who in 1548 published Nützlicher Bericht, […] Wie man den Mundt, die Zän und Biller frisch, rein, sauber, gesund, starck und fest erhalten soll) – Useful report…how to keep your mouth, teeth and gums clean and fresh, work dedicated to the subject. However, it will take another 200 years before the subject is more systematically broached in 1743 by Robert Bunon, a french dentist. His publication, Essay sur les Maladies des Dents, (A study on the diseases of the teeth) earned him the moniker of Father of Oral Hygiene.

What kind of oral hygiene habits did our ancestors have? When were the tools of oral hygiene (toothpaste, toothbrush, mouthwash, dental floss, toothpick tongue scraper) first introduced? The next few entries will address this.

The toothpick

The oldest oral hygiene tool is the toothpick. They have been around from the dawn of recorded time, either to simply remove food debris from the interdental space or as jewelry, as it became fashionable during the Medieval Time, to demonstrate one’s social status. The earliest forms of toothpick, during the Neanderthal and Paleolithic periods were probably made of bone or wood (1,2). Alone or in combination with an ear scoop, dental scraper, or even hunting whistle, made of a quill, wood, ivory, bamboo, bronze, iron, copper, silver or gold, toothpicks have a rich history. In many instances these tools were attached as a “grooming set” for personal use and displayed on one’s chest or belt.

Early evidence for such sets comes from grave sites where burial of one’s utilities to accompany the dead into the afterlife was common practice. In addition, wooden fibers found in grooves of lower teeth, facing the interdental space of early cavemen indicates the use of toothpicks 1.2 million years ago (3). The earliest grooming set dates from 3000 years BCE Mesopotamia. (4)

During the excavations conducted in 1847 at Nineveh by Henry Layard, the British archeologist, 660 tablets with cuneiform writing were uncovered. They were from the time of Enlil-Bani, King of Isinth (1798-1775 BCE) and contained medical recipes and description on the use of toothpicks. The tablets also contained curative incantations for diseases of the mouth, teeth and to treat halitosis and excessive salivation.

Some early toothpicks were not man-made. Rather, they were natural, obtained from the dried flowers of the Amni visnaga, a plant originally from the Nile Delta. Also known as “bushnika” in Morocco, and commonly referred as the “toothpick flower” plant, their medicinal use is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus. (see Figure 1.)

In ancient Greece and Rome, the mastic tree (Pistuciu zenticus) that gave rise to the early toothbrush (miswak in the Middle East and Africa) was used to fashion wooden toothpicks. The Greek word used for toothpick was karphos, which translates as a “blade of straw.” (5) In addition to wood, feather or silver toothpicks were also employed. For instance, Diodorus Siculus (6) described that Agathokles (317-289 BCE), the ruler of Syracuse used a toothpick cut from a quill. Pliny advised, “picking the teeth with the quill of a vulture turns the breath sour while a porcupine’s quill makes the teeth firm.” He also recommended using a “needle-sharp hare’s bone” to prevent halitosis. Feathers were used both as toothpicks and toothbrushes; the cut end of the quill to pick, and the feather end to brush (7). Others, like Trimalchio, a character in Gaius Petronius Arbiter’s first century work the Satyricon, “picked his teeth with a silver toothpick” (…dentes spina argentea perfodiebat).

The Latin name for toothpick was dentiscalpia (-um) and it is first defined in a 16th century lexicon of Johannes Gorraeus (8) (Jean de Gorris, French Physician, 1505-1577) Definitionum medicarum Liber XXIIII – 1564). The same lexicon of medical definitions also identifies auriscalpium, the ear-pick, a tool often part of the personal grooming set (See Figure 2. 3 and 4).

Introduced to France by the Spanish minister Antonio Perez (9) at the end of the 16th century, toothpicks became highly fashionable. Starting with the 17th century, for the more affluent, it was customary to wear a grooming set around one’s neck containing a toothpick, an ear pick, a nail cleaner, even a head scratcher, a set fashioned as a jewelry. A particularly good example is seen in the Portrait of Lucina Brembati, a painting by the Italian High Renaissance painter Lorenzo Lotto, dating to c. 1521/23. Lorenzo Lotto painted a charming portrait of Lucina Brembati, who wears a large jeweled toothpick on a gold chain around her neck. (https://www.lacarrara.it/en/catalogo/58ac00068/).

At least four Shakespeare plays mention toothpicks (Much Ado About Nothing, King John, All’s Well that Ends Well and A Winter’s Tale). The last one depicts a person using a toothpick as a “great man”:

“He seems to be the more noble in being fantastical: a great man, I’ll warrant; I know by the picking on’s teeth” [ Scene IV, The Sheppard’s Cottage, Shakespeare, A Winter’s Tale.]

In “All’s Well that Ends Well”, Act I, Scene I., toothpicks are depicted as a fashion item part of a broach.

“Virginity, like an old courtier, wears her cap out

of fashion: richly suited, but unsuitable: just

like the brooch and the tooth-pick, which wear not now.”

The Industrial Revolution increased the demand for toothpicks. That led to larger production of wooden toothpicks primarily in Portugal where nuns in the Larvao Monastery, south of Porto, used orange wood toothpicks to serve sticky confectionary. After consumption, the serving sticks were used as toothpicks. Orange-wood hand-made toothpicks were first imported from Brazil to Portugal. In 1850, Charles Foster, a Bostonian returned from Brazil and secured mass production of flat wooden toothpicks made of birch tree, mostly for the American market. Because the state of Maine had lots of birch trees and transport was too expensive, Foster set up its manufacturing locally in Strong, ME, “the toothpick capital of the US”, a city that in 1945 still produced 75 billion toothpicks.

Today, toothpicks are no longer favored by the oral healthcare community due to its potential damage to periodontal tissue. Instead, dental floss, regular toothbrushing and professional cleaning took over.

-

- Ricci

-

- Lozano

-

- Hardy, 104:2

-

- Petroski

-

- Wolf, p.54-63

-

- Diodorus, Book 5

-

- Christen, p.73.

-

- Gorraeus, p. 376

-

- Sachs, p.52.

The dentifrice – toothpaste

From the dawn of civilization men feared the tooth worm. An 18th century representation of the tooth worm was like a tormentor of Hell (10). As a result, early Indian, Babylonians, Egyptians and Greeks recommended wiping one’s teeth with abrasive materials. Ancient Indian recipes included mix of crushed charcoal and salt and the use of a twig-brush. Red salt and juniper were pulverized, combined and applied onto one’s teeth according to a Babylonian tablet inscribed in cuneiform writing (11). In the 4th century BCE Greece, Hippocrates suggested the use of a cloth or a woolen ball “dipped in honey” to wipe off one’s teeth with tooth powder. Galen, the 2d century Greek physician of several Roman emperors recommends the use of the powder of radishes dried in the sun, or of white glass finely pulverized and mixed with the essential oil of the Indian spikenard (muskroot).

Content of the tooth powder varied over centuries and cultures. They included crushed bone, eggshell or oyster shell, salt, alum, chalk, pumice, even soot or charcoal. In most instances vinegar, wine or honey were added to the mix. Romans used charcoal and bark, while Chinese added either mint or ginseng to improve the taste.

Early English literature contains recommendations for personal hygiene. William Vaughn, a doctor of Civil Laws in 1600 published Naturall and Artificial Directions for Health, a self-help text that includes detailed instructions on how to keep one teeth healthy and one’s breath “sweet” (12). Most of the recommendations were similar to those from Ancient times. The literature uses the terms dentifrice and tooth powder to define tooth cleaning agents from antiquity to the beginning of the 20th century, and tooth paste after that time. The word “dentifrice” comes from Latin dentifricium, that is dens – “tooth” and fricare – “to rub.”

In 1606, Peter van Foreest, a Dutch physician described six dentifrices for maintenance of dental health, against bad breath and for tooth-whitening. They contained cinnamon and mint water (for taste and active ingredient), Arabic gum (for consistency), pulverized bone, pumice, or salt (as abrasive agents) and rose water or white wine (as solvents). (13).

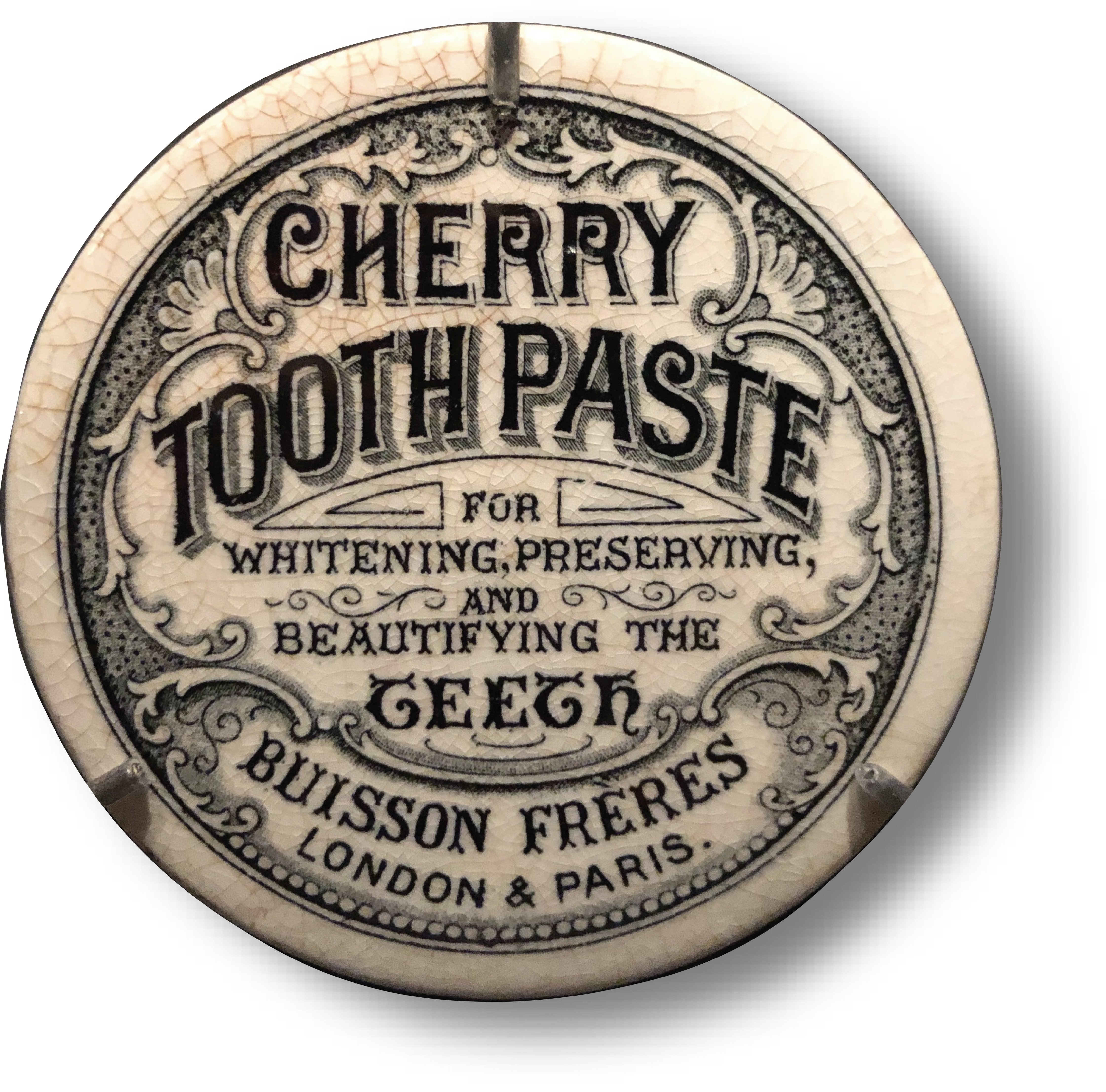

At the turn of the 20th century, toothpowder was substituted for a softer toothpaste. Dispensed usually from a tin, porcelain or paper box, toothpaste was sold by dentists under the practice’s own brand (See Figure 6). Many advertised with outlandish claims about their effect on protecting teeth. The 1888 Cressler’s Wild Rose Tooth Powder claimed to be used “for cleansing and preserving the teeth and purifying and perfuming the breath”(14). It contained borax, sodium bicarbonate, charcoal, and “soap”, a detergent. That was a precursor to sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS) the detergent introduced after WWII, an ingredient that makes toothpaste foam.

A major advance in toothpaste delivery occurred in 1892 when Dr. Washington Sheffield, a Connecticut dentist adopted the painter’s collapsible tube. The idea came to his son, also a dentist, Lucius Tracy Sheffield, while watching Parisian painters use it on the bank of the Seine. Four years later, Colgate issued its first” Ribbon Dental Cream” dispensed from a collapsible tube.

Today’s toothpaste cannot be imagined without fluoride. Its importance as a preventive agent was first described in 1843 by the French dentist Antoine Malagou Desirabode, as “fluate” (15). It was first marketed in 1895 by the Karl Frederick Toellner Company, of Bremen, Germany. Sold under the name of Tanagra, fluoride was included in toothpowder, toothpaste and mouthwash. Patented in 1915 in England, fluoride became widely available in mass marketed toothpastes only in 1955. (16, 17, 18).

Today’s toothpaste has many of the same types of ingredients that ancient recipes recommended, except they are far more effective. For instance the active ingredient today is fluoride, abrasive agents include calcium carbonate, dehydrated silica gels and hydrated aluminum oxides. To improve taste, sorbitol and saccharin are included, as humectants, glycol and glycerol are chosen, and as detergent, SDS is added. Starting in 1961 agents countering dentin hypersensitivity such as potassium nitrate were also added, and from 2009 arginine bicarbonate and amorphous calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate were included.

-

- 10. Hoffmann-Axthelm (b). p. 216, Fig 206.

-

- 11. Ibid p. 30

-

- 12. Vaughn p. 70-76.

-

- 13. Foreest p. 216

-

- 14. Croll p.16

-

- 15. Desirabode p.409

-

- 16. Lipert p1-14

-

- 17. Roher p.104

-

- 18. Meiers

The mouthwash

The history of the mouthwash cannot be separated from that of toothpowder or toothpaste.

Cleaning one’s mouth were advocated from ancient times either by mechanical or chemical means. Rubbing with a cloth, a stick, a brush, combined with an abrasive powder were recommended. The earliest evidence of the use of a mouthwash was in Ancient China and India. It contained an extract of the Barringtonia tree mixed with “mustard, Bengal pepper, ginger, alkaline ash and salt” (19,20).

The Roman poet Gaius Catullus recommended daily gargling with one’s own urine, as both, Diodorus Siculus (90-30 BCE) and Strabo (64 BCE-21CE) claimed that the Celtiberians living on the Iberian peninsula: “use urine to bathe the body and wash their teeth” (21,22).

A typical description of how one should keep one’s mouth clean is found in Zene Artzney, the first book dedicated exclusively to dental remedies published in 1530 (23). In William Vaughn’s 1602 treaties on the “Naturall and Artificial Directions for Health” these suggestions are made: “take a linen cloth, and rub your teeth well within and without, ….Take halfe a glasse-full of vineger, and as much of the water of the mastick tree of rosemarie, myrrhe, mastick, bole Armoniake, Dragons herbe, roche allome, of each of them an ounce (….) and wash your teeth therewithall as well before meate as after” (24).

The initial impetus for cleaning one’s mouth and teeth was primarily prevention of bad breath rather than understanding a cause-effect relationship between bacterial byproducts and dental decay. In 1683 Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, the discoverer of the microscope, in a letter to Francis Aston, secretary of the the Royal Society describes bacteria for the first time: “there are more animals in the unclean matter on the teeth in a man’s mouth than there are men in the whole kingdom – especially in those who don’t ever clean their teeth, whereby such stench comes from the mouth of many of them, that can scarce bear to talk to them” (25,26). It will take at least 200 more years to make the connection between bacteria and dental caries.

Gargling with one’s own urine, twice a day, morning and evening, advocated in ancient times, is reinforced in Pierre Fauchard’s second edition 1746 work (27). The practice gradually fell out of favor with the invention of more appealing mouth wash, “l’Eau de Botot”, originally named L’Eau Balsamique et Sipiritueuse”, an invention in 1755 of Dr. Julian Botot physician to King Louis XV. It included gillyflower extract (clove), star anise and cinnamon and claimed to heal dental pain and keep teeth and the gum healthy (28).

It is remarkable that even the early formulations of the mouthwash included a key components we still use today: antibacterial and antifungal agents (Barringtonia extract or ginger), minerals (Myrrh containing calcium and phosphate), antioxidants (mustard), essential oils (ginger, clove oil) and solvents.

The mouthwash as we know it today was introduced starting with the end of the 19th century, once the bacterial nature of caries, periodontal disease and halitosis became understood. Its content included specific components to address the bacterial, fungal or inflammatory nature of oral conditions. In 1879 Dr. Joseph Lawrence a physician from St Louis, Missouri in collaboration with Jordan W. Lambert, introduced Listerine as a surgical antiseptic named after Joseph Lister, the Scottish surgeon. It proved so successful, that in 1895 Lambert agreed to advertise Listerine specifically for oral use and in 1914 became available over the counter. It contained alcohol and four essential oils including menthol, thymol, methyl salicylate and eucalyptol. As knowledge of the nature and role of specific bacteria in the etiology of oral diseases became understood, specific antibacterial agents were added to mouthwash including urea, dibasic ammonium sulphate (1949), sodium hexametephosphate, hydrogen peroxide, chlorhexidine, zinc chloride, benzoic acid and, from 1955, as an anti caries agent, sodium fluoride.

Starting from humble beginnings, it is estimated that by 2027 in the US alone, the tooth paste business will reach $21.9 billions.

-

- 19. Weinberger

-

- 20. Hoffman-Axthelm (a) p.36, p.189

-

- 21. Diodorus, book 5

-

- 22. Strabo, V II, book III ch. 4

-

- 23. Die Zene Artzney

-

- 24. Vaughn p. 57-63.

-

- 25. Leeuwenhoek

-

- 26. Lane

-

- 27. Fauchard p.167

-

- 28. Botot p.30

The toothbrush

Cleaning one’s teeth goes back to ancient Babylonians, Indians and Egyptians. During the reign of the 3d Dynasty, 2680 BCE, Hesy-Ra was the first official “dentist” and ivory carver of Pharaoh Djoser. Both the Babylonians and Egyptians used a pointed piece of special twig that was turned into a cleaning instrument. Made of a twig from the arak or licorice tree, the chewing stick became widely adopted in Africa, Middle East, India and Far East (29). Known later as “miswak” or “siwak”, the aromatic tree twig turned out to contain fluoride, abrasive and antibacterial agents that enhance its mechanical and chemical cleansing effect. The chew stick was so widespread, it is mentioned in the Koran (as miswak), in the Gospel of Buddha (received from god, Sakka), in Ayurvedic Texts and the Talmud (as quesem) (30).(See Figure 9).

The origin of the modern toothbrush is not entirely clear. Japanese Zen master in 1223 described Chinese monks using a toothbrush made of horse hair attached to a bamboo or bone handle. The toothbrush that we recognize today was probably invented in China during the end of the 15th Century. A 1498 Chines woodcut depicts what looks like a toothbrush that resembles the one we use today. (31)

In Europe the toothbrush may have been introduced to France in 1590 by Antonio Perez, secretary of King Philip II of Spain. One of the earliest scientific description comes from Christoph von Hellwig (a.k.a. Valentin Krautermann) in 1700 in Freuenzimmer – Apotheckgen – A woman’s bedroom toiletries (32). A more direct description comes from Thomas Berdmore, dentist to George III King of England. In 1768 he describes the toothbrush “..the use of the straight tooth-brush, which has the hair fixed in the end, somewhat like a painter’s pencil. This sort of brush, if it be well made of short stiff hair, instantly removes whatever scraps of food have lodged between the Teeth.…” (33). This brush was made “of horse’s hair or hog’s bristle”, as Robert Woofendale, Berdmore’s pupil explains in his 1783 work, Observations on the Teeth(34). This design, no doubt matched that of the miswak used from antiquity throughout the middle and far east and Africa.

In 1780 an Englishman, William Addis of Clerkenwell created the first prototype of a multi row toothbrush using a bone handle and rows of holes filled with wild boar tufts of hair as bristles. Addis mass marketed this toothbrush design. His descendent were in the toothbrush manufacturing business with the same name, Addis until 1996, now known as Wisdom Toothbrushes. At the end of the 18th century toothbrush was not common. Among the nobility one could see elaborately ornate toiletry including Napoleon’s toothbrush from 1795. It had a gilded silver handle and 14 rows of horse-hair bristle (For a similar toothbrush, see Figure 8).

With the industrial revolution demand for improved oral hygiene also grew. The first patent for a modern toothbrush was awarded on November 17, 1857 to H. Nichols Wadsworth of Washington, DC (See Figure 10). His, was not an original design. Charles F. Maury, a French dentists published in 1841 his work entitled Traité complet de l’art du dentiste d’après l’état actuel des connaissances where he displays several toothbrushes that look exactly the one Wadsworth claimed to have invented (See Figure 11). Nevertheless, Wadsworth patent set the stage for the mass production of the toothbrush in the US. With the Industrial Revolution, demand for oral products stimulated innovations and improvements in toothbrush design. In the 100 years following the first tooth brush patent in 1857, the US issued 618 patents for toothbrushes.(35). The first mass produced tooth brushes had bristle made of horse or wild boar hair. Handles were bone, wood or ivory. Finally, in 1938 with the invention of nylon, under the name “Dr. West’s Miracle Tuft”, DuPont mass commercialized tooth brush made entirely of plastic bristle and plastic handle.

The first electric toothbrush was patented in 1932 by Clement Lieux of Lafayette, LA. It was a battery operated rotary brush with interchangeable brushes. It did not catch on. The modern electric toothbrush was invented in 1954 by Phillip Wong of Switzerland under the name of Broxodent. The next advance, the cordless electric toothbrush with a rechargeable battery, was introduced in 1955 by General Electric.

Today toothbrushes come in a staggering array of variations, softness, size, shape, bristles length and color but all having the same basic design, a handle/support and a brush. The basic design has not changed fundamentally.

-

- 29. Nunn p.124

-

- 30. Khatak

-

- 31. Hyson

-

- 32. Hellwig p.39

-

- 33. Berdmore p.259

-

- 34. Woofendale p.153.

-

- 35. Toothbrush patents

The dental floss

Oral hygiene was not a priority before the end of the 19th century, with the realization of the harm oral bacteria can cause. And yet, as early as 1815 Levi Spear Parmly, a dentist and “father of oral hygiene” advocated cleaning the interdental spaces using waxed silk threads. Parmly came from a successful family of dentists and he practiced in New Orleans. In his 1818 book, A Practical Guide to the Management of the Teeth, he suggested the need to brush, use a dentifrice polisher and a “waxed silken thread …placed .. through the interstices of the teeth, between their necks and the arches of the gums to dislodge that irritating matter which no brush can remove….(36,37,38)

Dental “floss silk” became mass marketed first by the S.S. White Company of Philadelphia in 1866. (39) The first patent for dental floss was awarded in 1898 to the Johnson and Johnson Co. Initially dental floss was sold in small glass, paper or metal tubes/boxes. Dr. Charles C. Bass, a medical doctor, in the early 1940s introduced the nylon dental floss to replace silk, a more economical solution.

Today floss comes as a nylon thread, tape made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), rubber, or plastic. Most of the floss no longer comes with wax. As an alternative to dental flossing, interdental brush was introduced in 1980. Flossing is still practiced by only 30% of the population.

-

- 36. Parmly p.73

-

- 37. Sanoudos p.3

-

- 38. Chernin p.15

-

- 39. S.S.White p.215

Tongue scrapers and other methods to combat halitosis

1847 was an exciting time to be an archeologist.That year Henry Layard, a British archeologist at Niniveh, former capital of the Assyro-Babylonian empire, uncovered 660 tablets with cuneiform writing some containing medical recipes. According to R. Campbell Thompson, a noted Oxford University scholar of Mesopotamian history, these tablets were at least 3,800 years old, probably from the period of Enlil-Bani, King of Isinth (1798-1775 BCE). In it, there were descriptions on the use of toothpicks and contained curative incantations for diseases of the mouth, teeth, halitosis and salivation. It was one of the first documents to describe oral care and, it came as no surprise, halitosis was objectionable even then.

Tongue scraper made of gold, silver, copper, tin, lead or iron was known to Ancient Indians (40). Described in the Charaka Samhita (circa 1500 – 800 BCE) numerous oral hygiene tools (sticks for brushing teeth and tongue scrapers) were included in this ancient Sanskrit work. Bad breath is also mentioned in the Talmud. One could divorce his wife if she had bad breath that could not be treated, but not the other way around.(41)

The Romans were aware of the need for oral hygiene. Gaius Plinius Secundus (23-79 CE) also known as Pliny the Elder, a Roman Senator, military commander, philosopher, naturalist and author of an encyclopædia, recommended washing one’s mouth every morning with fresh water. Quintus (Sammonicus) Serenus a 3d c., Roman savant and tutor to emperor Caracalla, suggests mastic and myrtle to improve bad breath (phoetor oris): “Lentiscus myrtus emendant oris odorem” (42).

A remarkably modern recipe is found in a Syrian (anonymous) manuscript from the early islamic period (8-9th c.?) translated from Greek into Syriac. The author, among several recipes recommends for bad breath: Salsola fructicosa, Nuts of incense, Betel nut, Caryophyllus aromaticus, Camphor, Cinnamon, Galanga, each 4g (1 drachma) and Musk 8g (2 drachma), pulverized and mixedwith wine and turned into pills, use as needed. What is remarkable is its active ingredients. For instance, Salsola fructicosa – has antibacterial and antioxidant activity, Nuts of incense (probably Frankincense), is a stabilizer, Betel nut –stimulates the nervous system, Caryophyllus aromaticus is clove which has anesthetic and anti-inflammatory activity, Camphor hasanalgesic and antifungal effects, Cinnamon is a major anti-oxidant but has anesthetic, antiseptic, and soothing effects, Galanga has anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, and Musk provides a pleasant odor to the mix. This 1200-1300 old recipe has everything one would need today to combat and mask halitosis. (43)

At the turn of the 17th century, in 1606, Peter Foreest, “the Dutch Hippocrates” recommends 6 recipes for dentifrices to combat halitosis. Itcontaining accacia (Arabic) gum or mastic as a stabilizing agent, myrrh as active ingredients, and nutmeg (has isoeugenol), “aqua menthae” (from dried leaves of menthe), and cinnamon to mask halitosis, and solvents that included white vine and rose water. Of note is that this recipe from the 17th century is remarkably similar to the one described in the Syriac “Book of Medicine”.

Parallel with masking halitosis, from the ancient times an attempt was made to clean the surface of the tongue either with a knife or a shovel-shaped tool. These items were frequently used as part of a personal grooming kit and included a tooth-pick, a nail clip and/or an ear pick, mounted on a ring and worn on one’s belt. In ancient India, a knife used as a tongue scraper, doubled as a toothpick(44).

That design seem to have lasted well into the 17-18th century when we start to see individual tongue cleaners/scrapers.(45).

Large scale demand for personal oral hygiene tools only started in the late 18 and early 19th century. The first patent was issued in 1877 to Lazarus Morgenthau of New York(46). The design was a flexible blade that could be folded into a U shape held with two hands to scrape the surface of the tongue. In the next 130 years over 135 tongue cleaner patents were issued in the US alone. The design of the cleaners varied little.

-

- 40. Shklar and Chernin, p.46

-

- 41. Shklar and Chernin, p.62

-

- 42. Dionysius p.134

-

- 43. Budge p.192

-

- 44. Hoffman-Axthelm (c) p.40.

-

- 45. Bennion p.137

-

- 46. Morgenthau

Evolution of oral hygiene management

Oral hygiene is the practice of maintaining one’s oral structures clean, healthy, esthetic and devoid of disease, breakdown, debris, accumulation, discoloration, or foul odor. Oral hygiene also covers all the tools at the disposal of a dentist or other oral healthcare provider, and patients to maintain healthy and esthetic oral structures to functioning properly.

Throughout history, delivery or practice of oral hygiene was fragmented, haphazard and opportunistic primarily due to the fog of ignorance. In its first phase, it was individual and reactive to tissue damage, breakdown, pain, loose teeth, bleeding, accumulation of debris, calculus, pathogens or foul odor. Self management, almost always rudimentary and superstitious was gradually substituted by emergency management, traditionally delivered by unqualified individuals.

Notwithstanding quacks or tooth-drawers of medieval times, the absence of oral care providers was substituted by the broadly educated physician. Just looking at the subject indices of many 15-17th century texts published by medical experts, one can see treatment offered for dental pain, caries, tartar, whitening and filling teeth, for bad breath or general oral hygiene.

Not withstanding Ryff’s (1548) oral hygiene instructions (47), only in the 18th century we see a first work dedicated to oral hygiene instruction and maintenance of oral health (48). Only in the mid 19th century we witness the birth of Oral Hygiene. The many tools, mouthwash solutions, methods of cleaning that helped keep oral tissues healthy coalesced into a more unified specialty promoted by an emerging oral health industry. A systematic approach to understand the reasons behind tissue breakdown or the patho-mechanism of oral diseases helped create oral health products, inclusion of specific ingredients to address specific needs: demineralization of enamel and dentin, reduction or prevention of caries, reduction of tooth sensitivity, prevention of plaque accumulation, elimination of halitosis or all of the above.

While the initial sale of these products was via dentists or pharmacist, as the dental industry took off in the middle of the 19th century, more and more item were commercialized via dental suppliers and not dentists. The production of tooth brush, toothpaste, mouthwash, floss, toothpick, tongue cleaning, all became part of a single industry and its use was heavily promoted as part of one’s daily oral hygiene routine. To these oral hygiene tools used at home, in 1955 the Cavitron was added to be used in a dental office setting.

In 2017, the global oral care market was $28 billions, and it is estimated to hit $40.9 billions by 2025 (49). William Addis of Clerkenwell, who created the prototype toothbrush from a leftover bone shank and wild boar hair and started mass marketing the modern design toothbrush would be shocked how much has changed in 240 years.

-

- 47. Ryff

-

- 48. Bunon

-

- 49. Grand View Research

References on oral hygiene tools

Bennion, Elisabeth (1986). Antique Dental Instruments. Sotheby’s Publications, London. p.137

Berdmore, Thomas (1768). – A treatise on the disorders and deformities of the teeth and gums, p.259.

Botot, Julien (1783) Moyens sur pour conserves des dents. pp.30.

Budge, E. A. Wallis (1913. The Book of Medicines” or Syrian Anatomy, Pathology and Therapeutics (Anonymous); Vol II. p.192. translated by Budge, E. A. Wallis (Ernest Alfred Wallis), Sir, 1857-1934. https://archive.org/details/syriananatomypat02budgiala/page/192/mode/2up/search/caryophyllus

Bunon, Robert (1743). Essay sur les maladies des dents. Paris: Briasson Chaubert; De Hansy. p.237.

Chernin, D and Shklar G. (2003). Levi Spear Parmly: father of dental hygiene and children’s dentistry in America. J Hist Dent. 2003 Mar;51(1):15-8.

Christen, AG, Christen, JA. (2003). A historical glimpse of toothpick use: etiquette, oral and medical conditions. J Hist. Dent. Vol. 51:2, 61.

Croll, T.P. and Swanson B.Z. (2000) 19th Century Dentistry Advertising Trade Cards: No 4. J. Hist. Dent. 48 (1):16.

Die Zene Arznei (1530) [Artzney Buchlein wider allerlei kranckheyten und gebrechen der tzeen, getzogen auß dem Galeno Avicenna Mesue Cornelio Celso und andern mehr der Artzney doctorn seher nützlich tzu lesen].

Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Loeb Classical Library 1939, Book 5. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/5B*.html#note42

Dionysius Duvallius (1590). Epigrammata et poematia vetera, edited Pierre Pithou, p.134. (The volume includes Serennus Sammonicus’s Liber Medicinalis under title De medicina praecepta saluberima, (p.126-164). https://books.google.com/books?id=jTIv2eC1ZqoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Epigrammata+et+poematia+vetera&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiP1cyP-JroAhW_lnIEHaEfAP0Q6AEwAXoECAQQAg#v=onepage&q=Epigrammata%20et%20poematia%20vetera&f=false

Desirabode, Malagou-Antoine (1843). Nouveaux elements complets de la science et de l’art du dentiste. p.409

Fauchard, Pierre (1746). Le Chirurgien Dentist. Volume 1. 2d Ed. , p. 167.

Foreest, Peter van (1609). Observationum et curationum medicinalium ll. XXXII Petrus Forestus. Ex Officina Palatiniana Raphelenghi 1606. p. 216.

Gorraeus, Johannes (Jean de Gorris). Definitionum medicarum Liber XXIIII, 1564. p 376 (Lat: dentiscalpia – Gr: οδοντογλυφα – odontoglypha)

Grand View Research (2020). Oral Care Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Mouthwash/Rinse, Toothbrush, Toothpaste, Denture Products, Dental Accessories), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2018 – 2025. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/oral-care-market (accessed, 2020, March 20).

Hardy, K., Radini, A., Buckley, S. et al. (2017). Diet and environment 1.2 million years ago revealed through analysis of dental calculus from Europe’s oldest hominin at Sima del Elefante, Spain. Sci Nat 104, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-016-1420-x

Hellwig, Christoph, von (1700). Freuenzimmer-Apotheckgen. Groschuff, XXXI, p.39. (First scientific description of modern toothbrush).

Hoffmann-Axthelm, Walter – a. (1981). History of Dentistry, Quintessence Publishing 1981, Chicago, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, p. 36 and 189.

Hoffmann-Axthelm, Walter – b. (1981). History of Dentistry, Quintessence Publishing 1981, Chicago, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo p. 30 and p. 216.

Hoffmann-Axthelm, Walter – c. (1981). History of Dentistry, Quintessence Publishing 1981, Chicago, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, p.40.

Hyson, John H. (2003). History of the toothbrush. J Hist Dent. 51(2):73-80.

Khatak, M (2010) Salvadora Persica, Pharmacogn Rev. 2010 Jul-Dec; 4(8): 209–214. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70920

Lane, Nick (2015). The unseen world: reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) Concerning little animals. 370Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0344

Leeuwenhoeck, Antoni Van (1952).The Collected Letters of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Vol IV (1683-1684) (in Dutch). C.V.Swets and Zeitlinger, Amsterdam 1952. (http://dbnl.org/tekst/leeu027alle04_01/leeu027alle04_01_0012.php

Lippert, Frank, (2013) An Introduction to Toothpaste – Its Purpose, History and Ingredients. In Toothpastes. Monogr Oral Sci Basel, Karger, Van Loveren C (ed), 2013, Vol 23, pp 1-14. DOI: 10.1159/00350456

Lozano M, Subirà ME, Aparicio J, et al. (2013). Toothpicking and Periodontal Disease in a Neanderthal Specimen from Cova Foradà Site (Valencia, Spain). PLOS ONE 8(10): e76852. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076852

Meiers, Peter. Early dental fluoride preparations. http://www.fluoride-history.de/p-dentifrice.htm.

Morgenthau, Lazarus (1877). Tongue scraper Patent # 194364, Aug 30, 1877.

Nunn, John F. (2002). Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Oklahoma Press, Norman 2002, ISBN 0-8061-3504-2, page 124.

Parmly, Levi Spear (1818). A practical guide to the management of the teeth. London, 1818, p.73. (The passage explains the three steps to preserve the teeth: 1. Toothbrush, 2. Dentifrice polisher and 3. Waxed silken thread.)

Petroski, Henry (2007). The Toothpick. Alfred Knopf, New York, pp.443.

Ricci S. Capecchi G. Boschini S. et al., (2014). Toothpick use among Epigravettian Humans from Grotta Paglicci (Italy). Int J Osteoarchaeol

Rohrer, Albert (1910) Zahnpulver und Mundwässer, Verlag von Georg Siemens, Berlin, p. 104.

Ryff, Walther Hermann (1548?): Nützlicher Bericht, […] Wie man den Mundt, die Zän und Biller frisch, rein, sauber, gesund, starck und fest erhalten soll (How to keep your mouth, teeth fresh, pure, clean, healthy, strong and firm for less). Johann Myller, Würzburg.

Sachs, Hans. Der Zahnstocher und seine Geschichte. Hermann Meuser, Berlin, 1913, pp. 52. (The toothpick and its history). Translated by Anna C. Souchuk, Published by Steven R Potashnick, 2010, ISBN-13: 978-1456494179).

Sanoudos M, Christen AG. 1999. Levi Spear Parmly: the apostle of dental hygiene. J Hist Dent. 1999 Mar;47(1):3-6.

Shklar, Gerald and Chernin, David. A Sourcebook of Dental Medicine, 2001, Maro Publications, p.46 (tongue scraper), p.62 (halitosis and Talmud).

S.S.White Dental Catalogue of Dental Materials Furniture and Instruments. 1867, p.215.

Strabo: The Geography of Strabo. The Library of History. Loeb Classical Library 1923, Volume II, Book III, Chapter 4. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/3D*.html#4.16.2

Toothbrush patents 1857-1957 – The US. Patent Office: https://www.uspto.gov

Tremble, Angus (2005). A Brief History of the Smile. Basic Books. p.288.

Vaughan, William (1600). Naturall and Artificial Directions for Health, derived from the best philosophers, as well moderne as auncient. R. Bradocke, London, pp. 70-76.

Vaughan, William (1602). Naturall and Artificial Directions for Health. R. Bradocke, London, p 57-63.

Weinberger, Bernhard W. (1948). – An Introduction to the History of Dentistry in America. CV Mosby, 1948.

Wolf, W. (1966). A history of personal hygiene customs, methods and instruments yesterday, today, tomorrow. Bull Hist Dent, 14: 54-63.

Woofendale, Robert (1783). Observations on the Teeth. p. 153 (toothbrush).

2023 © Copyright HistoryofDentistryandMedicine.com