Professionals Complementary to Dentistry (Dental Assistant, Dental Hygienist, and Dental Therapist).

The journey of those historically engaged in dental care, ranging from tooth extraction to alleviating oral discomfort, is extensive and varied. Throughout history, various trades and professions have intersected with what we now recognize as dentistry. However, tracing a chronological development is challenging, as these occupations did not evolve along a straightforward path to the modern dentist. Indeed, many of these professions coexisted at various times, contributing to the complex tapestry of dental history. Among these (in alphabetic order) were apothecaries, barbers, barber-surgeons, blacksmiths, bleeders, cabinet makers, dentists, denturists, druggists, engravers, fustian cutters, goldsmiths, hairdressers, ivory turners, jewelers, mountebanks, painters, patent medicine vendors, perfumers, physicians, tooth drawers, toymen, umbrella makers, victuallers, watchmakers, and wool sorters, to name a few.

For clarity, “dentist” will be used broadly to describe these early practitioners, even though many operated before the term was commonly used. The earliest known dentist, Hesy-Ra, dates back to 2686 BCE in Egypt’s 3rd Dynasty under Pharaoh Djoser. Hesy-Ra, known as Weribeh-senjw or “the great ivory-cutter,” served in a capacity that included dental care and perhaps oversaw the ruler’s monthly enemas as only part of his duties, illustrating the multifaceted roles of early dental care (1).

Figure 1. Hesy-Ra tomb from Saqqara. The upper right corner yellow square) contains three hieroglyphs describing him as the great ivory-cutter or “dentist” – Image in Public Domain.

A notable discovery from the Roman era further exemplifies early dentistry’s evolution. In a taberna near the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman forum, archeologists found 86 extracted teeth in the drainage, indicating that tooth extraction was a significant activity there in the first century CE. This site also doubled as a dispensary for medicinal concoctions, blending dental care with broader medical practices. (2).

The practice of dentistry was also documented among Arab physicians during the end of the first millennium and the beginning of the second. Avicenna (Ibn Sina) documents oral surgical procedures for removing tumors and cysts, the cauterization of carious teeth, and tooth removal. (3). Abulcasis (936-1013), the preeminent Arab physician and surgeon of Cordoba, in the 30-volume Kitab al-Tsarif, describes the method and positioning of the patient for extraction. He advises: sedere infirmum inter manus tuas et caput eius in sinu tuo et rade molam et dentem. (Translated: position the patient’s (head) between your hands, (place) the patient’s head in your lap, and loosen up the gum around the tooth) (4).

We will use the evolution of dental practitioners in France, England, and later on, in America, to illustrate the various layers of practitioners, where such evolution is best documented (5, 6, 7, 8)

In the 16th century, the landscape of dental care was characterized by four distinct groups operating independently, each with its unique practices and expertise. Contrary to common misconceptions, these groups did not share a common origin, adding to the complexity of dental history.

At the bottom tier were the untrained charlatans, quack, known as mountebanks, a dominant group in rural France and England during the 17th century, with the earliest description in 1382 as a “counterfeit physician” (8). These individuals peddled purportedly beneficial nostrums and derived their name from the Italian “monta banco,” signifying standing on a podium while selling a remedy and entertaining the public. (5,7,8). The term charlatan, originating from the Italian word “ciarlatano,” denotes chatter or gabble. Mountebanks were primarily entertainers showcasing puppet shows, contortionists, fire-eaters, and sellers of drugs with alleged magical properties, occasionally engaging in tooth extractions. The period literature interchangeably uses mountebank, quack, charlatan, quack-salvers, or saltimbancoes. Between 1600 and 1800, Pont Neuf, a central bridge in Paris, hosted charlatans selling “miracle tooth products” and conducting extractions publicly, distinguishing them from the skilled tooth drawers. One of the most famous was Grand Thomas, a larger-than-life mountebank operating on Pont-Neuf. (9).

The next group consisted of tooth drawers and skilled practitioners specializing in tooth removal. Known by various names across Europe, such as Operators for the Teeth in England, zahnbrecker in Germany, Arracher des Dents in France, and cavadenti in Italy. Starting in 1701, In France, they had to undergo a rigorous three-hour examination to obtain a license and the title of expert. The examination occurred before the Chief Royal Surgeon or his lieutenants, covering topics such as bloodletting, medications, tooth removal, and addressing infections and abscesses. A good illustration of what a tooth drawer might have looked like is shown in Figure (right) from Zene Artzney, the first dental book published (Figure 2). (10).

Figure 2.: Depiction of a tooth drawer in 1530. Image from Artzney Buch.

Above the tooth drawers, the third group of practitioners was the barber-surgeon, or chirurgien ordinaire (in France), or ordinary dental practitioners. Stratification within the profession arose from the Parisian surgeons’ concerns that barber-surgeons were encroaching on their territory, tarnishing their reputation. The barber-surgeons also had to undergo examinations. In addition to tooth removal, barber-surgeons were allowed to lance the gums (for rebalancing the humours), clean teeth, and place obturators for covering palatal bone deficiency, a common complication of syphilis.

The pinnacle of dental care in France emerged around 1700 with the introduction of the title chirurgien dentiste or dentiste by Pierre Fauchard in 1728 (11). Representing the first form of surgical specialization, dentists were required to join the Order of St. Comes, named after St. Cosmas and St. Damian, patron saints of dentistry. Prospective dentists also underwent courses and extensive apprenticeships and paid a fee before admission into the order. Some achieved the prestigious title of Maistres en Chirurgie, becoming members of the University of Paris Faculty, as evident in the 1761 almanac listing 30 expert dentistes including two women, Madelaine-Francoise Calais and Hervieux, and three Maistres en Chirurgie (12). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3.: List of practicing dentists in Paris in 1761 (12).

Above the chirurgien dentistes were the general surgeons, overseen by the Chief Royal Surgeon, who wielded absolute power. A pivotal moment in elevating the status of surgeons occurred in January 1686 when King Louis XIV sought surgical treatment for an anal fistula, leading to the ennoblement of his surgeon, Charles-Francois Felix, receiving a generous allowance from the treasury. This event marked a turning point in the recognition of surgeons’ expertise and making anal fistula, or the royal disease, a fashionable ailment.

Royal decrees, charters, and acts of parliament regulated the practice of dentistry starting in the 14th century, buffeting the practitioner’s evolution. We will focus on the best-documented French and English experiences for illustrative purposes.

In France, in 1311, the College of St Côme (Collège or Confrérie de Saint Côme) was founded by the French King Philippe the Fair. The College is named after the patron saints of medicine, Saints Cosmas and Damian, the twin brothers. Established for the benefit of surgeons of the long robe, distinguishing themselves from the lowly barbers or surgeons of the short robe. (13.) Starting in 1311, by the French King’s ordinance, those wishing to practice had to take an examination before the Master Surgeons. Records show that in 1313, the Parisian Martin Le Lombard, one of the first Frenchmen “who treated teeth,” charged double the amount that a barber of their time. (14).

In 1505, Barber-Surgeons (Surgeons of the Short-Robe) were admitted to the University of Paris. They were allowed to place leeches and perform bleeding and amputations. Two hundred years later, amputations and other surgical operations would be the purview of surgeons, and barber-surgeons would be relegated to placing leeches, drawing blood, and removing teeth.

Louis XIV of France in 1669 appointed an Operator for the Teeth (a barber-surgeon) to his court, the first to recognize a barber-surgeon as a specialist for teeth in France.

In England, The Worshipful Company of Barbers was established in 1308. Peter de London was the first tooth drawer (touzdrawere) mentioned in the guild’s documents in 1320. Sixty years after the barber’s company, in 1368, The Fellowship of Surgeons was established. While barber-surgeons were organizing and providing the dominant portion of extractions, parallel with them, tooth drawers were also practicing, providing opportunistic extractions. The first tooth drawer in England is mentioned in 1377 In Langland’s of Piers Plowman (1377) (15).

1511 Henry VIII signed The Physicians and Surgeons Act. The King stipulated that to practice either, one has to have “both great learning and ripe experience.” It was enacted to suppress the proliferation of quacks. Still, other than qualified individuals, they got into extracting teeth. A 1610 will of Humphrey Baker, a farrier (a horseshoe maker), shows that as a blacksmith, he possessed tools used in tooth extraction (16). The number of practicing trades included the blacksmith, the tooth drawer, the barber-surgeon, and some physicians. To consolidate their oversight, in 1540, by an Act of the British Parliament under the rule of Henry VIII, The Fellowship of Surgeons and the Company of Barbers merged. It concerned the practice and the training of barbers and surgeons. In 1800, the Company of Surgeons became the Royal College of Surgeons.

“Operator for the Teeth” first appeared in the 17th century. M. Blanlieu, the first Royal Operator for the Teeth of King Charles I, was mentioned in 1641. (17). Others, Peter de la Roche, Operator for the Teeth in London was mentioned in 1664. (18.) By the end of the 18th century, the title of “dentist” or “surgeon-dentist” had been adopted.

In 1745, King George II split the Guild of Surgeons again into separate Companies of Barbers and Surgeons. This coincided with an upsurge in demand and the appearance of Operators for the Teeth in provinces and London. These practitioners were not exclusively focusing on dentistry. In a mid-century trade directory and newspaper advertisement, Hillam (7) found dentists previously having been involved in trades like apothecary/druggist, hairdresser, perfumer, toyman, barber, fustian cutter, wool sorter, bleeder, patent medicine vendor, victualler, jeweler or watchmaker (19). Still, in 1855, 75% of those practicing dentistry had either a medical (43%, including physicians, surgeons, or apothecaries) or a chemist/druggist (32%) background, including pharmaceutical chemists, patent medicine dealers, or herbalists. Another 17% included cuppers, bleeders, aurists, chiropodists, medical electricians, bone setters, and tooth drawers. Only 4% of provincial dentists practicing in England had formal medical education.

It is difficult to determine the number of practicing dentists at a particular time using 18th- and 19th-century census data. In 1851, 1,051 dentists were listed in England. Many surgeons were practicing dentistry but were listed as surgeons. Others who were not practicing exclusively, such as ivory turners, umbrella makers, and engravers, who were practicing some aspect of dentistry would list their primary trade first and not be counted as “dentists” (20). Since the beginning of the 19th century, more druggists have offered full dental services. This may have coincided with the increase in patent medicine sales, which required both an apothecary to prepare and a place to sell these drugs.

Meanwhile, the first recorded dentist in the American Colonies was James Mill of New York in 1634. In 1766, John Baker was among America’s first established British dentists. He tutored Paul Revere and started practice in Boston.

The key moment in the evolution of the dental practitioner was the establishment of educational institutions to train dentists (1840) and the regulatory environment to limit and evaluate the number and quality of practicing dentists (1841). The US Census 1850 lists 2,923 dentists. The second half of the 19th century saw the development of dental auxiliaries. These included Dental Assistants (1888), who were called Dental Nurses in the UK, the appearance of Dental Hygienists in the US in 1913, and Dental Therapists in New Zealand in 1921 (see further).

Dental specialties and subspecialties

A further development during the 20th century in the evolution of the dental practitioner was the emergence of the dental specialist. These specialties have been, largely replicated around the world, (21,22, 23). Dental specialties and subspecialties, recognized (R) and unrecognized (U) in the US, in alphabetic order, with their start date* are

Cosmetic Dentistry (U) (1984)

Dental Public Health (R) (1937)

Endodontics (R) (1943)**

Forensic Dentistry (U) (1970)

General Dentistry (U) (1859)*

Implant Dentistry (U) (1951)

Oral Anesthesiology (R) (1953)

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (R) (1918, called exodontists, later renamed)

Oral Medicine (R) (1945)**

Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (R) (1946)

Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology (R) (1921, Am. Soc. Dental Radiographers, later renamed)

Orofacial Pain (R) (1975)

Orthodontics (R) (1900)

Pediatric Dentistry (R) (1926, Am. Soc. for Promotion of Dentistry for Children, later renamed)

Periodontics (R) (1914, American Academy of Oral Prophylaxis and Periodontology, later renamed)

Prosthodontics (R) (1928)

Restorative Dentistry (U) (1921)

Special Care Dentistry (U) (1971, called Int’l Assoc. of Dent. for the Handicapped, later renamed)

Temporomandibular Disorder (U) (1986).

*For purposes of this study the start dates for individual US specialties are considered the year when the respective specialty societies were established. For General Dentistry, the ADA is considered, as the first national society. ** ADA recognized Endodontics as a specialty in 1963 & Oral Medicine in 2020.

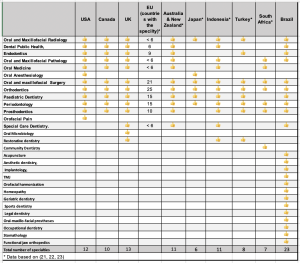

A comparison of ten geographic areas and countries is shown in the Table below. Most countries have 2-6 common specialties with the most (18) being in Brazil. Almost universally accepted are two specialties: oral surgery and orthodontics.

Table: Comparison of dental specialties among ten countries/geographic areas.

References

- Hoffmann Axthelm

- Becker, 2014

- Avicena, p.461

- Abulcasis p 172-176

- King

- Hargraves

- Hillam

- Thompson

9. Jones

10. Artzney Buch

11. Fauchard

12. Jèze, 1761, p.6

13. Pioreschi, p.430

14. Degan 1926, p.15

15. Hillam p.10

16. Id3em p.11

17. Hargraves, p.73.

18. Woodforde, p.24

19. Hillam p.18

20. Idem p.2

21. Garcia-Espona

22. Sanz

23. Moss

Dental Auxiliaries or Professionals Complementary to Dentistry

1. History of Dental Assistants

During the era when apprenticeship served as a primary form of dental education, aspiring dentists often engaged as assistants to their masters, though these “dental assistants” won’t be included in our historical narrative.

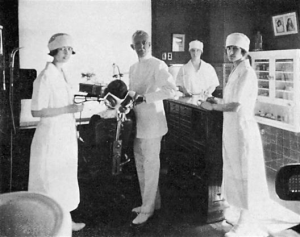

The origins of formal Dental Assisting can be traced to New Orleans, Louisiana, where Dr. Charles Edmund Kells Jr. practiced dentistry. A graduate of the New York College of Dentistry (NYCD) in 1878, Dr. Kells returned to New Orleans to work alongside his father, who had served as his mentor and preceptor at NYCD. In 1885, Dr. Kells made a significant decision by hiring his wife, Florence, as his dental assistant. Soon after, he brought on board Malvina Cuerina (Figure 1), a teenage assistant seen standing on the left side of the chair in the provided image. Throughout his extensive career, Dr. Kells continued the practice of hiring young female assistants, typically aged 16-17, whom he would train for a period ranging from three to six months. (1).

Figure 1: C. Edmund Kells and his staff (Malvina Cuerina, standing on the left). (1)

These Dental Assistants referred to as Dental Nurses in the UK and Dental Dressers, or alternately known as Waiting Maids, Ladies in Waiting, or Office Girls, were trained to carry out a specific set of dental tasks under the supervision of a dentist (2,3,4).

In a list of diverse names dental assistants had, Fiona Ellwood of the Society of the British Nurses enumerates twenty-one different designations: Subordinate, Ladies in Waiting, Dental House Maidens, Auxiliary, Dental Nurse, Certified Dental Assistant, Licensed Dental Assistant, Chair-side Attendant, Dental Surgery Attendant, Sick Berther to Dental Surgeon, Trained Auxiliary, Chair-side Assistant, Dental Auxiliary, Somatological Assistant, Dental Assistant, Dental Surgery Assistant, Registered Dental Assistant, Intra-oral Dental Assistant, Dental Dresser, Dental Sister, and Dental Matron.

The first organized effort in Dental Assisting emerged with the formation of a dental assistant society in Nebraska in 1917, with Juliette A. Southard appointed as its inaugural president. Subsequently, in 1924, the first National Convention of Dental Assistants convened in Dallas, Texas, followed by the incorporation of The American Dental Assistants Association (ADAA) in Chicago, Illinois, in 1925. Across the Atlantic, the British Association of Dental Nurses was established in 1940, alongside the emergence of other European Societies of Dental Nursing during the 1940s.

References

- Kells

- Reed B

- Johnson

- Southard

2. History of Dental Hygienists

To comprehend the emergence of dental hygienists, it is essential to revisit the genesis of oral hygiene practices. Throughout history, references to oral hygiene sporadically appear in the writings of ancient Indian, Greek, and Roman scholars. Despite this, a systematic approach to oral hygiene was largely absent until the medieval period, with little to no emphasis on its practice or understanding.

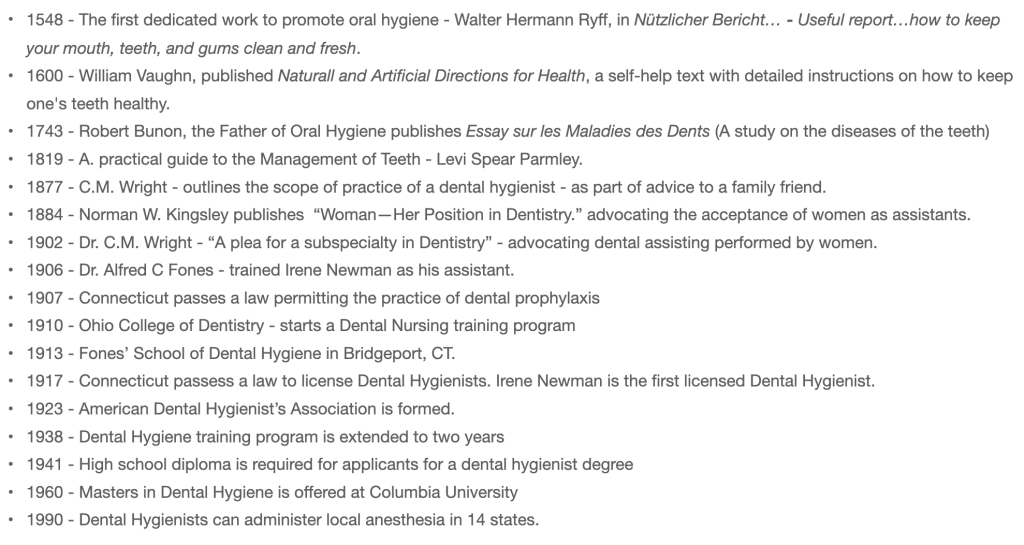

The narrative begins to change with Walther Hermann Ryff (c.1500-c.1548), a German surgeon based in Strasbourg. Around the mid-16th century, specifically in 1548, Ryff authored “Nützlicher Bericht…” or “Useful report…how to keep your mouth, teeth, and gums clean and fresh.” This publication marks one of the earliest dedicated efforts to promote oral hygiene. Fast forward nearly two centuries, and in 1743, Robert Bunon (1702-1748), a French dentist, contributed further to this field with his work “Essay sur les Maladies des Dents” (A study on dental diseases), which also emphasized the importance of maintaining oral hygiene.

An interesting fact from this period involves John Greenwood (1760-1819), known as George Washington’s favored dentist. Greenwood, in 1778, annotated his copy of John Hunter’s “The Natural History of the Human Teeth” with sidenotes that highlighted his acknowledgment of the importance of oral hygiene.

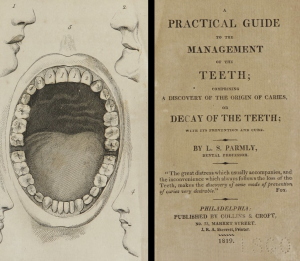

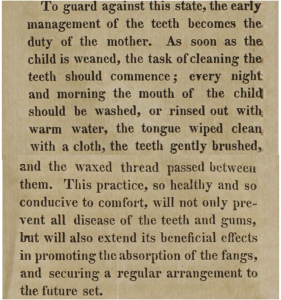

Levi Spear Parmly, a dentist active in the early 19th century, significantly advanced the conversation around oral hygiene. In 1819, Parmly published “A Practical Guide to the Management of the Teeth,” which included a chapter titled “Domestic advice on the teeth.” This chapter detailed comprehensive care for teeth, gums, tongue, and other oral structures, notably advocating for the use of dental floss. (see Figure 1a and 1B). (2).

Figure 1a: Cover page of A Practical Guide to the Management of the Teeth by L.E. Parmly

Figure 1b. Specific instructions on using a dental floss.

By the latter half of the 19th century, the dental community began to recognize the importance of oral hygiene within dental care, leading to the acknowledgment of the need for professionals dedicated to the cleaning and polishing of teeth. Norman Kingsley, recognized as the Father of Modern Orthodontics, published an editorial in 1884 that supported the idea of women becoming dental assistants, highlighting a shift towards inclusivity and specialization in dental practice.

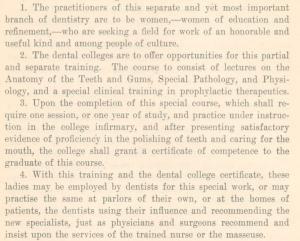

A significant development occurred in 1902 when C.M. Wright (3) revisited an idea he had conceived in 1877. He proposed a dental subspecialty designed for “ladies of education” that would specialize in prophylactic therapeutics. Wright envisioned a training program that encompassed one session focused on the anatomy of teeth and gums, special pathology and physiology, along with clinical training in prophylactic therapy, polishing teeth, and overall oral care. This training, lasting one year at the Dental College Infirmary, aimed to prepare graduates for employment by dentists, with Wright emphasizing this as an opportunity for “missionary work.”

Wright’s vision in 1902 outlined the educational and practice framework (See Figure 2) for what would become the profession of Dental Hygienist, marking a pivotal moment in the evolution of dental care (3,4,5).

Figure 2: Wright outlined the educational and practice framework for dental hygienists.

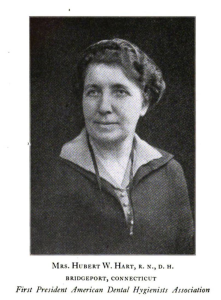

Figure 3. Hubert W. Hart was the first president of the American Dental Hygienists Association (ADHA) (5).

Alfred Fones, a dentist from Connecticut, is widely recognized for pioneering the first formal training program for Dental Hygienists. In 1906, Fones took on Irene Newman as his apprentice, effectively establishing her as the inaugural dental hygienist. Subsequently, in 1907, Connecticut passed legislation allowing hygienists to conduct dental prophylaxis, marking a significant milestone in the recognition of this profession.

In 1913, Fones took a monumental step forward by founding the first school dedicated to training dental hygienists, located in Bridgeport, CT. However, this institution’s lifespan was brief, closing its doors within three years. Undeterred by this setback, Fones persisted in his advocacy efforts, ultimately leading to the passage of legislation in 1917 by the Connecticut legislature, officially permitting the practice of dental prophylaxis.

The establishment of the American Dental Hygienists Association (ADHA) in 1923 marked a pivotal moment for the profession, with Mrs. Hubert W. Hart (See Figure 3) serving as its inaugural president. By 1923, approximately 1,100 Dental Hygienists were practicing across the United States. The formation of State Dental Hygienist’s Associations quickly followed, solidifying the professional presence of Dental Hygienists across the nation.

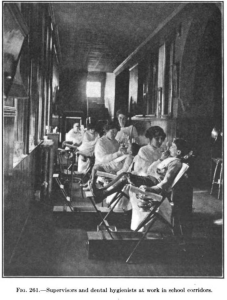

Initially, Dental Hygienists were primarily employed within educational institutions (see Figure 4). However, by 1925, twenty-six states had sanctioned their practice outside of academic settings. This recognition of the role of Dental Hygienists in clinical practice signaled a significant expansion of their professional scope. Additionally, in 1927, the Journal of the American Dental Hygienists Association was established, providing a dedicated platform for the dissemination of knowledge and advancement of the profession.

Figure 4. Dental Hygienist at work in a school in 1916. (6).

Figure 5. Timeline of Dental Hygiene

References

- Spielman

- Parmly

- Wright

- Fones (b)

- Ohio State

- Fones (a)

3. History of Dental Therapists

The advent of Dental Therapists stemmed from the urgent global need to address oral diseases, particularly prevalent in low- and middle-income countries. The US Surgeon General’s Report, “Oral Health in America,” released in 2000, underscored the prevalence of dental disease and the health disparities among impoverished and minority children (1,2,3).

The first Dental Therapy program, initially known as Dental Nurses, was established in New Zealand in 1921. Over the past century, significant milestones in the development of Dental Therapy educational programs have shaped its trajectory. Presently, 54 countries worldwide offer dental nursing/dental therapy programs, reflecting the success and widespread adoption of this model. The 54 countries permitting DTs today are distributed by continent, with 12 in North and Central America, 25 in South-East Asia, Oceania, Australia, and New Zealand, two in Europe, and 14 in Africa. The New Zealand experiment was unique for the first 27 years.

Figure 1. Distribution of the 54 DT programs across the globe.

Early adopters of Dental Therapy programs included Malaysia (1948), Sri Lanka (1949), Singapore (1950), Tanzania (1955), and the United Kingdom (1959). Notably, 33 of the 54 countries permitting Dental Therapists today belong to the Commonwealth of Nations, a legacy of the British Empire (Figure 1).

In the United States, attempts to introduce Dental Therapy faced resistance. In 1949, Massachusetts proposed legislation for a two-year training program to restore teeth under dentist supervision, but opposition from the dental association led to its withdrawal (8). Similarly, in 1972, a “dental nurse” training proposal by Drs. John Ingle and Nathan Friedman met opposition from dental associations, derided as “mediocre in conception and harmful in execution” by the American Dental Association president at the time. (4,5).

However, the discussion around Dental Therapy gained momentum in the early 21st century. In 2005, Alaska introduced dental therapists trained in New Zealand, following a legal battle with the American Dental Association. Subsequently, in 2009, the University of Minnesota granted the first degree in Dental Therapy.

Figure 2. Fourteen States have authorized the use of Dental Therpaists in the US (purple) and several states (red) are considering legislation.

Presently, 14 states in the US authorize dental therapy practice (Figure 2). These are Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana (only on tribal land), New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, Idaho, and Montana (the last two, only on tribal land). Sixteen additional states considering similar legislation (6). In 2015, the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) established education standards for Dental Therapy, leading to the establishment of training programs in Alaska, Minnesota, and Washington, totaling five programs across three states (7). The U.S. currently has five training programs for dental therapists in three states: Alaska (1), Minnesota (3), and Washington (1).

An analytical review of Dental Therapy (DT) programs across the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Tanzania reveals that the average duration of these programs is three years (see Table above). Historically, some nations offered distinct two-year programs for Dental Nursing and Dental Therapy. However, recent trends show a shift towards amalgamating these two tracks into a unified three-year educational framework. Australia and New Zealand have notably adopted this integrated approach.

Figure 3. Comparison of the scope of DT practice across seven countries.

In several countries, pursuing Dental Hygiene (DH) education can culminate in obtaining either an associate degree or a Bachelor of Science degree. On the other hand, a combined educational pathway incorporating both Dental Hygiene and Dental Therapy training can lead to the attainment of a master’s degree. This educational structure highlights the evolving landscape of dental professional training, aiming to broaden the skill set and knowledge base of dental practitioners.

A timeline of the DT program is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Timeline of the Dental Therapy Programs around the World.

References.

- WHO

- Oral Health in America

- Murthy

- Nash (a)

- Nash (b)

- Oral Health Workforce Research Center

- CODA

- Mathu-Muju

References on dental practitioners and auxiliary personnel.

Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (1556). Avicennae Medicorum Arabum principis Liber Canonis Basilae: Apud Ioanes Hervagios, p. 461. Caries lesion – called corosione dentium.

Abulcasis (1532). Chirurgicorum Libri Tres. Strassbourg, pp. 172-176—description of patient’s position, dental forceps, and extraction instruments. This volume is combined with the work of Priscianus, Theodorus, and Neuenra, Hermann von (1532). Rerum Medicarum Libri Quator. Argent Apud Ioannem Schottum.

Baron, Pierre (2003). Dental Practitioners in France at the end of the Eighteenth Century.

Becker, M. J. (2014). Dentistry in Ancient Rome: Direct Evidence for Extractions Based on the Teeth from Excavations at the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum.International Journal of Anthropology, 29(4), 209-226. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/anthrosoc_facpub/29

Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) (2015). Standards for dental therapy. https://coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/dental_therapy_standards.pdf?rev=814980f6110140e7ba00659703cc3b3c&hash=81A3585FD5B1B478DA7D99065A9B75DE

Degan, Georges (1926). Histoire de l”art dentaire en France. Ed. de la Semaine Dentaire, Paris. p.15 (The first dentist, Martin Le Lombard, was recorded in France in 1313).

Fauchard, Pierre (1728) – Le Chirurgien Dentist. Two volumes. http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/histoire/medica/resultats/index.php?cote=31332×01&do=chapitre

Fones, Alfred C. (a) (1916). Mouth hygiene. United States: Lea & Febiger. p.486.

Fones, Alfred C. (b) (1926). The origin and history of the Dental Hygienist Movement. JADA, 13(12):1809-1821,1926. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1926.0294

Garcia-Espona, I., Garcia-Espona, C., Alarcón, J.A. et al. Is there a common pattern of dental specialties in the world? Orthodontics, the constant element. BMC Oral Health 24, 49 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03713-5

Hargraves, Ann S. (1998). White as Whalebones: Dental Services in Early Modern England. Northern University Press.

Hillam, Christine ed., Dental Practice in Europe at the End of the 18th Century. Clio Medica 72 / The Wellcome Series in the History of Medicine. p. 37-54.

Hillam, Christine. 1991. Brass Plate and Brazen Impudence. Dental practice in the provinces 1755-1855. Liverpool University Press.

Hoffmann-Axthelm, Walter (1981). History of Dentistry (Translated from German H.M. Koehler, Chicago:, Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc., pp. 435.

Jones, Collins. Pulling Teeth in Eighteenth-Century Paris, Past & Present, Feb. 2000, No. 166, pp. 100-145. http://www.jstor.com/stable/651296.

Kells, C. Edmund, Jr. – The Dentist’s Own Book, St Louis, MO, 1925.

King, Roger (1998). The making of the Dentiste, c. 1650-1760. Ashgate, Brookfield, USA.

Jèze (1761) État ou tableau de la ville de Paris : considérée relativement au necessaire, à l’utile, à l’agréable, & à l’administration: Dentistes. p.6.

Jèze (1759). Tableau de Paris pour l’année 1759, formé d’après les antiquités, l’histoire, la description de cette ville, etc… Paris : C. Hérissant, 1759, p.196-197.

Johnson, C. N. (1925). The Possibilities of Professional Service Through Co-operation Between the Dentist and his Assistant’, Journal of the American Dental Association (1925), 12(1):44-48. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1925.0008

Mathu-Muju KR (2011). Chronicling the dental therapist movement. J Pub Health Dent. 71:278–288. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00270.x.

Moss, J.P., Orosz, M. and Bánóczy, J. (1999), Specialisation in Dentistry in Europe – A review. European Journal of Dental Education, 3: 180-183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0579.1999.tb00089.x

Murthy VH (2016). Oral health in America, 2000 to present: progress made, but challenges remain. Public Health Reports 131(2):224–225.

Nash DA, Friedman JW, Mathu-Muju K, Robinson PG, Satur J. et al. (2014). A review of the global literature on dental therapists. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 42(1):1-10. doi:10.1111/cdoe.12052.

Nash DA, Friedman JW, Kardos, TB, Kardos RL, Schwartz E, et al. (2008). Dental therapists: a global perspective. Int Dent J. 58(2):61-70, doi:10.1922/IDJ_1819-Nash10

Ohio State Dental Hygienists Association 1926. History and Progress of Dental Hygiene, The Journal of the American Dental Hygiene Association. Vol 1 (2):3-9. 1927.

Oral Health Workforce Research Center (OHWRC). https://oralhealthworkforce.org/authorization-status-of-dental-therapists-by-state/ (accessed, March 5, 2023).

Oral Health in America: a report of the surgeon general. (2000). Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. HHS, NIDCR, NIH.

Parmly, Levi Spear (1819). Domestic advice on the teeth. In: A practical guide to the management of the teeth: comprising a discovery of the origin of caries or decay. Collins and Croft, Philadelphia. 1819. p. 187-188. https://archive.org/details/2566032R.nlm.nih.gov

Prioreschi, Plinio (1996). History of Medicine: Medieval Medicine, Horatius Press, p. 430.

Reed, Debbie (2021). History of dental nursing, BDJ. 8 (21). pp. 48-51. ISSN 2054-7617. (doi:10.1038/ s41407-021-0782-x.)

Sanz M, Widström E, Eaton KA. Is there a need for a common framework of dental specialties in Europe? Eur J Dent Educ. 2008 Aug;12(3):138-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2008.00510.x. PMID: 18666894.

Southard, Juliette A. The Dental Assistant, The Dental Student, vol 2., October 1924, p 23-24. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Dental_Student/7W6F2QrfOTcC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Ladies+in+Waiting,+dental+assistant&pg=PA23&printsec=frontcover

Thompson, C.J.S., The Quacks of Old London, 1928, Brenton’s Limited, New York, London, Paris.

Spielman AI, Koshki J, Lepor A, Shaner A. (2023). John Greenwood’s sidenotes on a 1778 John Hunter text at the New York Academy of Medicine. J Hist Dent. 71(3):159-171. https://doi.org/10.58929/jhd.2023.071.03.001

World Health Organization (2022). Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. 18 November 2022. ISBN:978-92-4-006148-4.

Woodforde, John (1968). The Strange Story of False Teeth. Universe Books. New York City.

Wright, C.M. (1902). A Plea for a Sub-Specialty in Dentistry. 23(4):235-238. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10156230/

Zene Artzney (1530). Die gut und gesundt zubehalten, Und alle gebrechen. First edition.