by Andrew I Spielman

How to cite this page: Spielman, AI. History of Orthodontics. In: Illustrated Encyclopedia of the History of Dentistry. 2023. https://historyofdentistryandmedicine.com/

Orthodontics, the branch of dentistry that straightens malpositioned teeth and corrects jaw relationships, has a relatively short history compared to other dental specialties. History, though, is replete with famous individuals that could have used modern orthodontic treatment. There is the famous “Habsburg Jaw” of the German-Austrian royal family, with Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, a shining example of prognathism kept in the family because of bread, along with the fortunes they were intended to preserve.

Straightening malpositioned teeth or making room for others has its earliest written evidence in the Roman physician Celsus’ work in the first century. He suggested removing persistent deciduous teeth to allow permanent teeth to erupt and pushing daily on the permanent tooth until in position (1).

Celsus’ solution reappears in one of the early dental books, Zene Artzney (2), in its fifth edition published in 1541 by Christian Egenolff of Frankfurt am Main, makes the following observation, adopted from Celsus:

It often happens that to children more than seven years of age, when the teeth begin to drop out other teeth grow by the side of those which are about to drop out: therefore we should loosen the tooth about falling out from the gums, and move it to and fro until it can be taken out, and then push the new one every day toward the place where the first one was, until it sits there and fits in among the other.s, for if you neglect to attend to this, the old tooth will remain, become black, and the young one will be impeded from growing straight, and can no more be pushed to its right place.”

In the 17th century, Fabricius Aquapendente, professor of surgery at the University of Padua, suggested extracting malpositioned teeth (3)

For the following century, there was very little evidence for orthodontic treatment. Only with the publication of Le Chirurgien Dentiste of Pierre Fauchard, we see an emphasis on correcting individual malpositioned teeth. Fauchard suggests attaching a small silver or gold strip and pulling them into position by attaching silk ligatures to neighboring teeth. These plates are described in a new chapter (VIII) that appears only in his 1746 second edition (4). He calls the realignment of teeth – redressez les dents and requires three elements: luxation of teeth, ligature, and the strip. Using this method, Fauchard went on to describe 12 successful orthodontic cases.

A more focused approach to orthodontics is seen in Etienne Bourdet’s (1722-1789) 1757 volume entitled Recherché et observations sur toutes les parties de l’art du dentiste. He recommends extracting the first bicuspid in the case of anterior crowding and extending to the entire arch using the ligature-held device Fauchard recommends (5). The chapter, Maniere de redresser les dents, et de les remettre en place, par la moyen des fils et des plaques on orthodontics extends to 20 pages.

Joseph Fox (6), a student of John Hunter, follows Bourdet’s ligature-held vestibular bar but adds two gag blocks at each end to keep the incisors out of occlusion and facilitate their vestibular movement in case of an inverted bite. (see image to the right, Fig 7., Plate XII, Fox, 1803). The alignment arch and gag blocks at the end were replaced by a more elastic metal bar supported by gold crowns placed on the first permanent molars. The bar in front and away from the tooth to be moved applied constant pressure and forward movement to the malposed incisors, while the gold crown on the molars replaced the gag blocks with an improved anchor (7).

A focused improvement of orthodontic treatment is seen in Johann Jacob Joseph Serre’s work (1759-1830), a Belgian surgeon and court-dentist in Berlin. He takes a wax impression of the malpositioned arch and teeth and, with the help of a goldsmith, creates a plaster model and prepares an appliance (8).

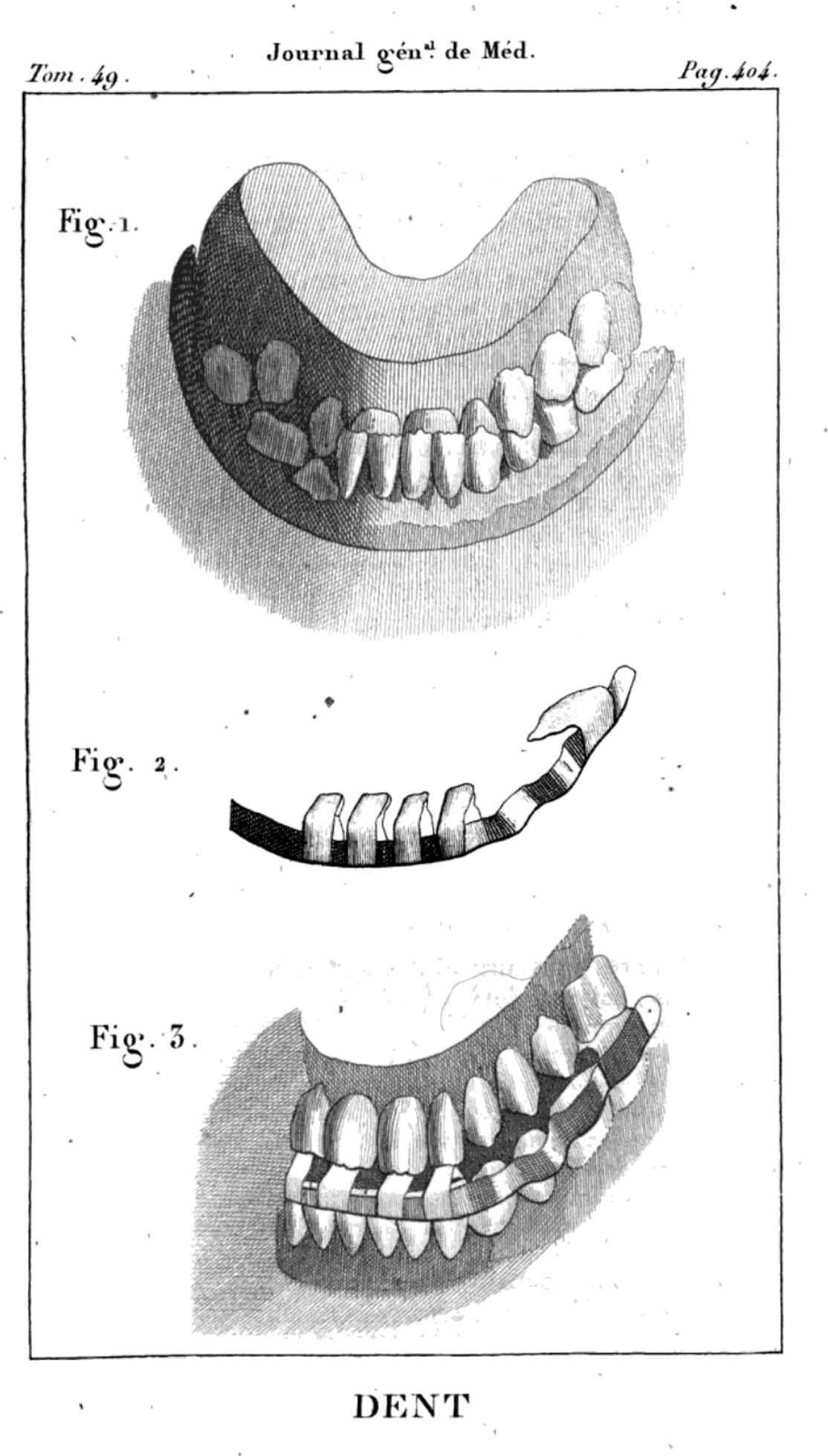

The idea of an inclined bite plane (“plan incliné”) was first used in 1809 by L.J. Catalan (1776? -1830). and first reported only five years later (9) (See image to the right). The device proved unpopular because of the damage it could inflict on the gingiva.

A decade later, in 1819, Christoph-Francois Delabarre (1784-1862) was the first to try to categorize the various types of malocclusions and suggested the placement of a space-maintainer. He was against removing deciduous teeth to make room for permanent dentition. Delabarre adopted Catalan’s bite plane and was the first to introduce a metal appliance for rotating a tooth. (10) In 1841, the French Joachim LeFoulon was the first to suggest expanding the maxillary bones (11). At about the same time, we witnessed the first dedicated 30-page study written on orthodontics. The author, Frederic Christophe Kneisel (1797-1883), published both in German and French in 1836 a work entitled Der Schiefstend der Zahne; Position irregulier des dents (The irregular position of the teeth) (12). Incremental advances followed. Just five years later, in 1841, Alexis J.M. Schange employed a flat rubber band (“bande de caoutchouc”) for the first time to treat maxillary protrusion by applying it labially and anchoring to both sides of the maxillary premolars and molars (13).

With the gradual spread of orthodontic treatment, it was time to further systematize various forms of occlusion. That task fell on Hungarian-born Viennese professor Georg Carabelli (1787-1842), court dentist to Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria. Carabelli, based on the position of the incisors and canines, classified occlusions into eight categories: 1. normal, 2. edge-to-edge (straight), 3. open, 4. protruding, 5. retruding, and 6. zig-zag (cross-bite); 7. senile, and 8. edentulous (14).

At about the same time, the freshly established American Society of Dental Surgeons (1840) decided to sponsor a dedicated publication on orthodontics. The following year, Solyman Brown of New York published the Essay on the importance of regulating children’s teeth. (15) It was intended as an educational pamphlet for parents.

A unique aspect of orthodontic history is the beginning of orthognathic surgery. The founding father of orthognathic surgery was James Edward Garretson in 1869, a pioneer surgeon from Philadelphia Dental College, now part of Temple University, who published “A System of Oral Surgery,” a textbook that had seen six editions in 30 years while in use.

During the second half of the 19th century, a number of incremental advances in orthodontics were introduced by many contributors, both in the United States and Europe. A few names, however, stand out: Norman Kingsley, the “founding father”, Edward Hartley Angel, the “father of modern orthodontics”, and John Nutting Farrar, of Brooklyn, NY.

Norman Kingsley (1829-1913) was the first practicing dentist specializing in unique facial and maxillary malformation cases. Thanks to his artistic talent, he hand-crafted devices for facial deformities, adopted the jackscrew to expand the jaw, an invention of a fellow New Yorker, D. William Dwinelle and Charles Gaine (Bath), used the bite plane to “jump the bite”, employed rubber bands to pull teeth, screws to push them, and obturators to seal the oro-nasal communications. In a word, Kingsley was the first all-around orthodontist. Owing to his experience and exposure to a variety of unique caseload, in 1880, he published the first dedicated book to orofacial deformities: “A Treatise on Oral Deformities as a Branch of Mechanical Surgery” (16). His reputation as a skillful clinician-led him to be named the founding dean of the New York College of Dentistry, now part of New York University. (On the right, image of an older Kingsley, c. 1900. Photo in the public domain).

John Nutting Farrar (1839-1913) introduced scientific rules in orthodontic adjustments of tooth movement. He favored screws that could be adjusted in a quantifiable manner and was less enthusiastic about rubber bands that could not be precisely calculated. He concluded that applying force to move 1/60 inch a day caused pain that lasted three hours. As he fine-tuned the force, he concluded that applying intermittent force to a tooth, with a movement not to exceed 0.2 mm or 1/120 inch a day, was appropriate (17).

The third individual that deserves mention is Edward Hartley Angle (1855-1930), the father of modern orthodontics, who placed the specialty on a scientific footing. (See signed portrait to the right, image from the archives of NYU College of Dentistry, reproduced with permission). He simplified and standardized his appliances in 1887, defined his new ideas on orthodontics, and, in 1899, published his classification of occlusion. Malocclusion was divided into three classes, normal (class I), retrusion (class II), and protrusion (class III) (18). He considered the first permanent molars, not the incisors or canines, as the anchor point of the arch relationship. Angle rejected Farrar’s intermittent force approach and instead recommended continuous force. He created reusable elements such as a molar band for retention, an arch-wire connecting the two sides, springs and screws, and elements that could be included in different appliances. The simplicity of his viewpoint made orthodontic treatment more approachable, standardized, and reproducible. In 1900, Angle established the first school of orthodontics, The Angle School of Orthodontics in St. Louis, followed in 1901 by the establishment of The Society of Orthodontists, which later morphed into the American Association of Orthodontists.

In the early 20th century, until Calvin S. Case of Chicago made a crucial observation, many orthodontic treatments led to failure or recurrence. One had to move the entire tooth, root, and crown to avoid recurrence. Adjusting appliances to create a full translational movement of the tooth eventually led Angle to his 1928 edgewise arch (19). The name emphasized its edgewise placement to distinguish it from the ribbon arch.

In 1909 a spring action lingual arch, originally invented by Lefoulon (11), was introduced by John Valentine Mershon of Philadelphia. Unlike spring and screw-activated tooth movement, the continuous lingual pressure could create a more effective force.

While Angle was against all forms of tooth extractions for orthodontic treatment, that view changed in 1923 with the publication of Axel Lundstrom’s thesis questioning if Angle’s classification of malocclusions was truly universal and covered all causes, and thus justified rejecting extractions as a mode of treatment for some of them. (20) Orthodontic diagnostics and treatment got a boost in 1931 with the introduction of the cephalometric analysis of a patient. (21)

Overall, two major trends in orthodontic treatment emerged in the early 20th century, the fixed appliance preferred in the New World and the removable appliance developed in Europe. Key individuals contributing to the removable appliance include the dilation screw of Charles Frederick Nord from Holland and the introduction of the “active plate” of Arthur Martin Schwartz (1887-1963) of Vienna. Schwartz’s appliance, worn mostly at night, took advantage of muscle activity. An extension of this innovation, originally conceived by the French Pierre Robin and in 1935 reintroduced, by Karl Hauple and Viggo Andresen, was the (“Norwegian”) system that involved both arches at the same time and emphasized the role of the facial musculature in determining their shape. (22) During the latter part of the 20th century, European schools gradually adopted the fixed appliance approach to shorten the orthodontic treatment time.

While technological advances refined orthodontic treatment, a key invention in 1997 of InvisalignR made it available to general dentists and, through them, to a much broader segment of patients with mild malocclusions. (23) Introduced by Kelsey Wirth and Zia Chishti of San Jose, CA, InvisalignR was approved by the FDA the following year. The disruptive nature of the invention is even more remarkable, considering that none of the initial inventors and partners were orthodontists. Some of the key patents of Invisalign expired in 2017. Other clear aligners are expected to become more accessible, overall benefitting the public’s appetite for “perfect teeth”.

- Celsus p.443

- Zene Artzney

- Aquapendente p.32

- Fauchard p.80 and 99, Fig. 15 – f4, f5

- Bourdet Vol. II. p. 19

- Fox, p.68 & Plate XII, Fig 7.

- Bell p.93

- Serre p.370

- Dubois-Foucou & Deschamps, p.404.

- Delabarre

- Lefoulon p.234

- Kneisel

- Schange p.128, Fig 11.

- Carabelli p.126

- Brown

- Kingsley

- Farrar p.23

- Angle (a)(b)

- Angle (c) p. 1147

- Lundstrom

- Broadbent

- Andresen

- Align Technology Inc.

References and notes on orthodontics

Align Technology Inc (2000). Systems and methods for positioning teeth. US Patent 6783360B2. https://patents.google.com/patent/US6783360B2/en; related to: U.S. Pat. No. 5,975,893 entitled “Method and system for incrementally moving teeth,” issued to Chishti et al. on Nov. 2, 1999; U.S. Pat. No. 6,406,292; and Ser. No. 09/556,022, entitled “System and Method for Determining Final Position of Teeth,” filed Apr. 20, 2000, now U.S. Pat. No. 6,457,972.

Andresen, Viggo. (1936). The Norwegian system of functional gnatho-orthopedics. Acta Gnathol., 1:5-36. (The Norwegian System of Orthodontics)

Angle, Edward H. (1887) (a).Notes on orthodontia with a new system of regulation and retention. The Ohio Journal of Dental Science, VII(10):457-464. (https://archive.org/details/ohiojournalofden7188unse/page/456/mode/2up?q=Orthodontia)

Angle, Edward Hartley (1899) (b). Classification of Malocclusion. Dental Cosmos 41(3):248-264, 350-357).

Angle, Edward Hartley (1928) (c). The latest and best in orthodontic mechanism. Dental Cosmos, 70(12):1143-1158. (edgewise arch introduction).

Aquapendente, Hyeronimus Fabricius ab (1619). Operationes chirurgicae in duas partes divisa, quibus adjectum est pentateuchon antea editum et alia. Italy: Paulus Megliettus. (p.32, suggests extraction of malpositioned teeth).

Bell, Thomas (1829). The anatomy, physiology and diseases of the teeth. S. Highley, London, p. 93-103. (Improved arch bar and a gold crown on permanent molars to move vestibular malpositioned teeth.

Bourdet, Etienne (1757). Recherche et observations sur toutes les parties de l’art du dentiste Vol II, p. 19. (First suggestion is to remove bicuspids to make room for crowded teeth and use a full arch metal strip to pull individual malpositioned teeth. It is an extension of Fauchard’s idea.)

Broadbent, B.Holly. (1931). A new X-ray technique and its application to orthodontia. Angle Orthodontist, 1, 45-66.

Brown, Solyman (1841). Essay on the importance of regulating the teeth of children. New York. p.11

Carabeli, Georg Edlen von Lunkaszprie (1842). Systematisches Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde. Vol II. Anatomie des Mundes, p.126-127. Wien. (First systematic classification of occlusions).

Celsus, Cornelius A. (1687). De Medicina Libri Octo. Apud Joannem Wolters, Amstelædami, Cap. XII, p.445. (Removal of deciduous teeth is necessary, and pushing day-by-day the permanent tooth into position). (https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QaeEvhp1S0fawl6eZY7tIDsDyTu6YX3BtYjbyInW65tNeX92vkiQ-hw245OgU1x3I47jxz6chPeQpeL32rJRhXha3vFTJ4ZMKkoIdSCctaACHFXJ94mRSDlXiy1x7cd8xIX4qf5QrZotUIrGXzyfUHs78UGYyJruuGmvfZwxF1wCdzvlJ8dJT3OLs9XIioxJo8X9-1s00WJDZoTzqpiFpYCuydKx9Kvbe-Su1dbpw4BEjsfbr8SwimKIfgeH7f1BtKyb9ttWo5J4kHQZK43LzXIh3EYmwgeorJBmba_g5MovMy9aiOU). The Latin text on page 445, chapter 12, Book VII, line 3: Si quando etiam in pueris ante dens nascitur, quam prior excidat, is, cadere debuit, circumradendus et evellendus ets; is qui natus est in locum prioris, quotidie digito adurgendus, donec ad justam magnitudinem perveniat. Translated based on Guerini, 1921: When a permanent tooth appears before the fall of the milk tooth, it is necessary to dissect the gum all around the latter and extract it; the other tooth must then be pushed with the finger, day by day, toward the place that was occupied by the one extracted; and this is to be done until it has firmly reached its right position”. (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/51991/51991-h/51991-h.htm)

Delabarre, Christophe-Francois (1819). Traite, de la seconde dentition, et method naturelle de la diriger. Paris. (Contraindicates early removal of deciduous teeth and suggests space maintainer).

Dubois-Foucou, & Deschamps (1814). Un nouvel instrument presente par M. Catalan fils, pour remedier a la difformite connue sous le nom Menton de Galoche. Journal General de Medecine, de Chirurgie et du Pharmacie, Vol 49;402-405.

Farrar, John Nutting (1876). An inquiry into physiological and pathological changes in animal tissues in regulating teeth. Dental Cosmos, 18 (1):13-24.

Fauchard, Pierre (1746). Le Chirurgien Dentiste. Vol II, p.79-80, Planche 15. 2d Ed. Paris.

Fox, Joseph (1803). The natural history of the human teeth. London, p.68, Plate XII, Fig7. (Orthodontic device uses two ivory gag-blocks at the end of a metal straightening strip attached to upper incisors. The gag block keeps teeth from occlusion, permitting incisors in an inverted bite to expand and move vestibular.)

Kingsley, Norman (1880). A Treatise on Oral Deformities as a Branch of mechanical Surgery. New York.

Kneisel, Johann Friedrich Christoph (1841). Der Schiefstend der Zahne; Position irreguliere des dents (The oblique position of the teeth). Berlin, Posnan and Bromberg. . (First dedicated orthodontic study written in German and French).

Lefoulon, Joachim (1841). Nouveau traite theorique et pratique de l’art du dentiste. Paris. (First to suggest that the maxilla and mandible can be expanded through gentle force. He was the first to suggest the lingual arch.)

Lundstrom, Axel Frederik (1925). Malocclusion of the teeth regarded as a problem in connection with the apical base. International Journal of Orthodontia, Oral Surgery and Radiography, Elsevier, 11(7):591-602; 11(8):724-731; 11(9):793-812; 11(10):933-941; 11(11):1022-1042; and 11(12):1109-1133. (refuting Angle’s insistence on not extracting teeth for orthodontic purposes).

Schange, Alexis J.M. (1841). Precis sur le redressement des dents. p.128, Fig 11. Paris. (First use a flat elastic band for maxillary protrusion).

Serre, Johann Jacob Joseph (1803). Praktische darschtellung aller Operationen der Zahnheilkunst, Berlin. p.370 (wax impression, plaster mold and orthodontic appliance preparation with a goldsmith).

2023 ©Copyright HistoryofDentistryandMedicine.com